Sunday Excerpt: Unequal Protection - The Boston Tea Party Revealed

How Corporations Became 'People' - and How You Can Fight Back"

Back in 2002, when I wrote this book, most Americans thought the Boston Tea Party was a revolt against “excess taxes” and that “corporate personhood” was something the Supreme Court conferred on companies back in 1886. This book blew up both myths, pointing out that the Boston Tea Party was a revolt against the British government giving the East India Company the largest corporate tax cut in history (so they could unfairly compete with small colonial tea merchants) — basically a revolt against the Wal-Mart-ization of the colonies — and that the Supreme Court did not rule that corporations are persons and thus entitled to rights under the Bill of Rights in 1886 (it was a corrupt scam by a bribed SCOTUS justice and Court Clerk). In the 20 years since Unequal Protection first came out, this “new” knowledge is now widespread. With permission from the publisher, Berrett-Koehler, I’ll be sharing most of the book (the updated edition) with you, one chapter at a time (and not always in order), over the next dozen or so Sundays.

The Boston Tea Party Revealed

As Abraham Lincoln biographer Albert J. Beveridge noted in 1928:

Facts when justly arranged interpret themselves. They tell the story. For this purpose a little fact is as important as what is called a big fact. The picture may be well-nigh finished, but it remains vague for want of one more fact. When that missing fact is discovered all others become clear and distinct; it is like turning a light, properly shaded, upon a painting which but a moment before was a blur in the dimness.[1]

There is such illumination in learning, for example, that in 1886 the Supreme Court had not, in fact, granted corporations the rights of persons— or in discovering that the battle between working people and what Grover Cleveland called the “iron heel” of corporate power was actually at the core of the American Revolution.

While the Pilgrims were early arrivers to America, and their deeds and experiences make outstanding folklore, they weren’t the country’s founders. This country was formally settled nineteen years before the pilgrims’ arrival, when land from the Atlantic to the Mississippi was staked out by what was then the world’s largest transnational corporation. The Pilgrims arrived in America in 1620 aboard a boat they chartered from that corporation. That boat, the Mayflower, had already made three trips to North America from England on behalf of the East India Company, the corporation that owned it. By the early- 1600s colonization of North America, the British Empire was just starting to become a world empire.

A century or so before that, as western European nations extended their reach and rule across the world in the 1400s and 1500s, England was far from being a world power. Following a series of internal battles and wars with Scot- land and Ireland, as well as power struggles within the royal family and with the Catholic Church, England at that time was considered by the Spanish, French, and Dutch to be an uncultured tribe of barbarians ruled by sadistic warlords.

Although Sir Francis Drake is touted in British history as a heroic explorer and battler of the Spanish Armada, as a treasure hunter and privateer he was in reality a de facto licensed pirate, and even in the late 1500s England lacked a coherent naval strategy or vision.

The British first got the idea about the importance of becoming a world power in the late 1400s when they observed the result of Christopher Columbus’s voyage to America—he brought back slaves, gold, and other trea- sures. That got Europe’s attention and threw Spain full-bore into a time of explosive boom. Then, in 1522, when Ferdinand Magellan sailed all the way around the world, he proved that the planet was a closed system, raising the possibility of tremendous financial opportunity for whatever company could seize control of international trade.

In many of the European countries, particularly Holland and France, consortia were put together to finance ships to sail the seas.

England got into the act a bit late, in 1580, with Queen Elizabeth I becoming the largest shareholder in The Golden Hind, a ship owned by Sir Francis Drake. She granted him “legal freedom from liability,” an early archetype for modern corporations.[2]

The investment worked out very well for Queen Elizabeth. There’s no record of exactly how much she made when Drake paid her share of the Hind’s dividends, but it was undoubtedly vast, since Drake himself and the other minor shareholders all received a 5,000 percent return on their investment. Plus, the queen’s placing a maximum loss to the initial investors of their investment amount only made it a low-risk investment to begin with. She also was endorsing an investment model that led to the modern limited-liability corporation.

The queen also often granted monopoly rights over particular industries or businesses in exchange for a fee. The 1624 Statute of Monopolies did away with this ability of the crown, although in the years thereafter the British government used tax laws to produce a similar result for the corporations favored by Parliament or the royal family.[3]

Limiting Risk by Incorporating

A business can operate at a profit, a break-even, or a loss. If the business is a sole proprietorship or a partnership (owned by one or a few people) and it loses more money than its assets are worth, the owners and the investors are personally responsible for the debts, which may exceed the amount they originally invested. A small-business owner could put up $10,000 of her own money to start a company, have it fail with $50,000 in debts, and be personally responsible for paying off that debt out of her own pocket.

But let’s say you invest $10,000 in a limited-liability corporation, and the corporation runs up $50,000 in debts and then defaults on those debts. You would lose only your initial $10,000 investment. The remaining $40,000 wouldn’t be your concern because the amount of your investment is the “limit of your liability,” even if the corporation goes bankrupt, defaults in any other way, or causes millions of dollars in damage to the environment or even the deaths of people.

Who foots the bill? The creditors—the people to whom the corporation owes money—or the community that was devastated. The company took the goods or services from them, didn’t pay, and leaves them with the bill, exactly as if you had put in a week’s work and not gotten paid for it. Or it wreaks havoc and death and then simply shuts down, as so many asbestos companies have done recently.

And if the corporation declares bankruptcy and dissolves itself, there is nobody for the creditors to go after. That’s the main thing that makes a corporation a corporation, and it’s why in England the abbreviation for a corporation isn’t Inc., as in the United States, but Ltd., which stands for limited-liability corporation (which is also used in the United States and other nations).

If you were a stockholder in a corporation that went under, it wouldn’t even be reflected on your personal credit rating (unless you had volunteered to personally guarantee the corporation’s debt). Your liability is limited to how- ever much you invested.

Moreover, a corporation can outlast its founders. If you started a one- man glassblowing business, for example, when you die or can’t work anymore, the income stops. But a glassblowing corporation is an entity unto itself and can continue on with new glassblowers and managers after the founders move on. The implication, of course, is that a corporation can pay profits as a divi- dend to its shareholders for centuries, theoretically forever.

This is what Queen Elizabeth had in mind. Incorporating The Golden Hind would limit her liability and that of the other noble and lesser noble investors and maximize their potential for profit. So after the big bucks she made on Drake’s expeditions on The Golden Hind, she started pondering what could be done about the small role England played in world trade relative to Holland, France, Spain, and Portugal.

In part to remedy this situation and in part to exploit a relative vacuum of power, she authorized a group of 218 London merchants and noblemen to form a corporation that would take on the mostly Dutch control of the global spice trade. They formed what came to be the largest of England’s corporations during that and the next century, the East India Company. Queen Elizabeth granted the company’s corporate charter on December 31, 1600.[4]

The East India Company Builds England…and America

It went slowly at first. For several decades the East India Company struggled to establish a commercial beachhead among the many Spice Islands and distant lands where there were potential products, raw materials, or markets.

The Dutch had so sewn up the world at this point in the early 1600s, however, that the only island the company was able to secure on behalf of England was Puloroon (leading King James I, who commissioned the translation of the Bible into English, to declare himself “King of England, Scotland, Ireland, France, and Puloroon”). In addition, the company’s hard-drinking captain, William Hawkins, managed to befriend the alcoholic ruler of India, the Mogul emperor Jehangir, building a powerful presence for the East India Company on the Indian subcontinent (which the company would take over and rule as a corporate-run state within two centuries).

During this time England had exported colonists to the Americas in large numbers, including many as prisoners (a practice they later moved to Australia, when it was no longer practical to send them to North America). There was also a steady and growing exodus from England of various types of malcontents who, on arrival in America, redefined themselves as explorers and pioneers or set up theocratic communities.

Much of this transportation was provided at a profitable price by the East India Company, which laid claim to parts of North America and created the first official colony in North America on company-owned land, deeded to the Virginia Company in 1606. (The companies had interlocking boards, as Sir Thomas Smythe administered the American operations of both from his house. Smythe was also the first North American governor of both the East India Company and the Virginia Company.)

The company called it Jamestown, after company patron and stockholder King James I (who took the throne and the royal share of the company’s stock when Queen Elizabeth died in 1603), and placed Jamestown on the Chesapeake Bay in the company-owned Commonwealth of Virginia, named after the now- deceased “virgin queen,” Elizabeth I, who had granted the company its original charter. On the maps from that time, the two companies’ claim of Virginia extended from the Atlantic Ocean all the way to the Mississippi River.*

America was one of the East India Company’s major international bases of operations; and once the company figured out how to make a colony work, it grew rapidly. Through the 1600s and the early 1700s, the company and its affiliates largely took control of North America but also sent Captain James Cook on his explorations of Australia, Hawaii, and other Pacific islands. He was killed in Hawaii while on a company mission of exploration.

The company’s influence was pervasive wherever it went. For example, one hundred years or more before Betsy Ross was born, the flag of the East India Company was made up of thirteen horizontal red and white alternating bars, with a blue field in the upper-left corner with the Union Jack in it. Although, according to the well-known legend, Ross reversed the order of the red and white bars, the American flag is startling similar to that of the East India Company in the 1700s.*

*The East India Company designed its flag with thirteen red and white bars long before there were thirteen states. Many historians believe it was because most of the stockholders in the East India Company were initiates in the Masonic Order, and the Masons considered thirteen to be a metaphysically powerful number. Virtually every signer of the Constitution was also a Mason, which may be why they chose to limit the original colonies to thirteen. But that’s all speculation; nobody knows for sure, or, if they do, they’re not telling.

In its earliest years, the company began assembling its own private military and police forces. After a particularly bloody massacre of company employees by the Dutch at Amboina, Indonesia, in 1623, the company realized it needed to hire some new and uniquely competent people to ply the trade routes. To stop smugglers from competing with its trade to North America, the company authorized its governor of New York to hire Captain William Kidd to clean up its trade routes by killing colonial smugglers and sinking their ships. When Kidd began secretly competing with the company on the side (an activity the company called smuggling and piracy), it had him captured and executed in 1701.

The company also approached the British Parliament and asked for authority and protection by British military forces.

Thus, many of the seemingly “political” appointees of England to the early Americas were first and foremost employees of the East India Company. One of many examples of how the company and the British military were connected is General Charles Cornwallis. During the American Revolution, he lost the Battle of Yorktown in 1781 but later went on to “serve with great distinction in the company’s service in India, and it was said of him that whilst he lost a colony in the West, he won one in the East.”[5]

From India to Yale: The East India Company Influences

As its first century of existence was wrapping up, the company’s worldwide reach had proven enormously profitable for its stockholders. For example, during these years Elihu and Thomas Yale grew up in the American colonies and, like many American colonists, went to work for the East India Company. Elihu became the company’s governor of Madras, India, where he made a huge fortune for himself and the company, while his brother, Thomas, negotiated the company’s first trade deals with China. Elihu returned home and made a large grant to the school that he and his brother had attended, which, in appreciation, renamed itself Yale College in 1718.

By the 1760s the East India Company’s power had grown massive and global. It had taken control of much of the commerce of India, was aggressively importing opium into China to take control of that nation (which would lead to the Opium Wars of the mid-1800s, which China lost, ceding Hong Kong to Britain for ninety-nine years), and had largely taken control of all international commerce to and from North America. This very rapid expansion and attempt to keep ahead of the Dutch trading companies, however, was a mixed blessing, as the East India Company went deep in debt to support its growth and by 1770 found itself nearly bankrupt.

Among the company’s biggest and most vexing problems were American colonial small businessmen and entrepreneurs, who ran their own small ships to bring tea and other goods directly into America without routing them through Britain or through the company. And there were many small-business tea retailers in North America who were buying their wholesale tea directly from Dutch trading companies instead of the East India Company. These two types of competition were very painful for the company.

The First Pro-corporate Tax Laws

The East India Company set a precedent that multinational corporations follow to this day: it lobbied for laws that would enable it to easily put its small- business competitors out of business. By 1681 most of the members of the British government and royalty were stockholders in the East India Company, so it was easy that year to pass “An Act for the restraining and punishing Privateers and Pirates.” This law required a license to import anything into the Americas (among other British-controlled parts of the world), and the licenses were only rarely granted except to the East India Company and other large British corporations.*

*The law was explicit about its purpose and the death penalty for operating without a license. It read, in part:

It shall be felony for any Person, which now doth, or within four Years last past heretofore hath or here after shall Inhabit or belong to this Island, to serve in America in an hostile manner, under any Foreign Prince, state or Potentate in Amity with his Majesty of Great Britain, without special License for so doing, under the hand and seal of the Governour or Commander in chief of this Island for the time being, and that all and every such offender or offenders contrary to the true intent of this Act being thereof duly convicted in his Majesties supreme Court of Judicature within this Island to which court authority is hereby given to hear and to determine the same as other cases of Felony, shall suffer pains of Death without the benefit of Clergy.

Be it further Enacted by the Authority aforesaid, that all and every Person or Persons that shall any way knowingly Entertain, Harbour, Conceal, Trade or hold any correspondence by Letter or otherwise with any Person or Persons, that shall be deemed or adjudged to be Privateers, Pirates or other offenders within the construction of this Act, and that shall not readily endeavour to the best of his or their Power to apprehend or cause to be apprehended, such Offender or Offenders, shall be liable to be prosecuted as accessories and Confederates, and to suffer such pains and penalties as in such case by law is Provided.

As trade to the American colonies grew, and under pressure from the East India Company, the British government passed a series of laws that increased the company’s power and influence and reduced its competition and barriers to international trade, including the Townshend Acts of 1767 and the Tea Act of 1773.

The Tea Act was the most essential for the East India Company because the American colonies had become a huge market for tea—millions of pounds per month—which was largely being supplied at cheap prices by Dutch trading companies and American smugglers, also known as privateers because they operated privately instead of working for the company. (The company also often encouraged the British government to prosecute these entrepreneurial traders and smugglers as “pirates” under the 1681 law.)

Many people today think that the Tea Act—which led to the Boston Tea Party—was simply an increase in the taxes on tea paid by American colonists. Instead, the purpose of the Tea Act was to give the East India Company full and unlimited access to the American tea trade and to exempt the company from having to pay taxes to Britain on tea exported to the American colonies. It even gave the company a tax refund on millions of pounds of tea that it was unable to sell and holding in inventory.

One purpose of the Tea Act was to increase the profitability of the East India Company to its stockholders (which included the king) and to help the company drive its colonial small-business competitors out of business. Because the company temporarily no longer had to pay high taxes to England and held a monopoly on the tea it sold in the American colonies, it was able to lower its tea prices to undercut those of the local importers and the mom-and-pop tea merchants and teahouses in every town in America.

This infuriated the independence-minded colonists, who were, by and large, unappreciative of their colonies’ being used as a profit center for the multinational East India Company corporation. They resented their small businesses still having to pay the higher, pre–Tea Act taxes without having any say or vote in the matter (thus the cry of “no taxation without representation!”).

Even in the official British version of the history, the 1773 Tea Act was a “legislative maneuver by the British ministry of Lord North to make English tea marketable in America,” with a goal of helping the East India Company quickly “sell 17 million pounds of tea stored in England…”[6]

A clue to the anti-globalization agenda of the American revolutionaries was found right on the Web site of the modern East India Company: “The infamous Boston Tea Party in 1773 was a direct result of the drawback of the government in London of duties on tea which enabled the East India Company to dump excess stocks on the American colonies, and acted as a rallying point for the discontented.”[7]

The site also noted that American antipathy toward the corporation that had first founded, owned, ruled, and settled the original colonies continued even after the American Revolution. After the Revolutionary War, the company tried to resume trading with America, offering clothing, silks, coffee, earthenware, cocoa, and spices, but, “Even after Independence the East India Company remained a highly competitive importer of goods into the United States, resulting in occasional flare-ups such as the trade war between 1812 and 1814.”[8]

America’s First Entrepreneurs Protest

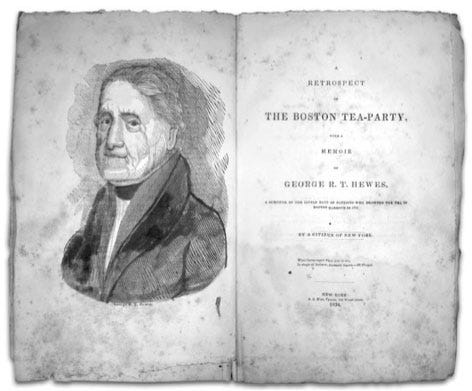

This economics-driven view of American history piqued my curiosity when I first discovered it. So when I came upon an original first edition of one of this nation’s earliest history books, I made a sizable investment to buy it to read the thoughts of somebody who had actually been alive and participated in the Boston Tea Party and the subsequent American Revolution. I purchased from an antiquarian bookseller an original copy of A Retrospect of the Boston Tea-Party with a Memoir of George R. T. Hewes, a Survivor of the Little Band of Patriots Who Drowned the Tea in Boston Harbour in 1773, published in New York by S. S. Bliss in 1834.

Because the identities of the Boston Tea Party participants were hid- den (other than Samuel Adams) and all were sworn to secrecy for the next fifty years, this account (published sixty-one years later) is singularly rare and important, as it’s the only actual first-person account of the event by a participant that exists, so far as I can find. Turning its brittle, age-colored pages and looking at printing on unevenly sized sheets, typeset by hand and printed on a small hand press almost two hundred years ago, was both fascinating and exciting. Even more interesting was the perspective of the anonymous (“by a citizen of New York”) author and of George Robert Twelvetrees Hewes, whom the author interviewed extensively for the book.

Although Hewes’s name is today largely lost to history, he was apparently well known in colonial times and during the nineteenth century.

Esther Forbes’s classic 1942 biography of Paul Revere, which depended heavily on Revere’s “many volumes of papers” and numerous late-eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century sources, mentions Hewes repeatedly. For example, when young Paul Revere went off to join the British army in the spring of 1756, he took Hewes along with him.

Frontispiece and title page of “A Retrospect of the Boston Tea-Party with a Memoir of George R. T. Hewes, a Survivor of the Little Band of Patriots Who Drowned the Tea in Boston Harbour in 1773.” (New York: S. S. Bliss, 1834)

“Paul Revere served in Richard Gridley’s regiment,” Forbes writes, noting Revere’s recollection that the army had certain requirements for its recruits. “All must be able-bodied and between seventeen and forty-five, and must measure to a certain height. George Robert Twelvetrees Hewes could not go. He was too short, and in vain did he get a shoemaker to build up the inside of his shoes; but Paul Revere ‘passed muster’ and ‘mounted the cockade.’”[9]

Hewes wasn’t of noble birth, according to Forbes.

George was of poor family. He had started out apprenticed to a shoemaker, ran away to sea and fished on the Grand Banks. At the time of the great inoculation, he was of age, back in Boston, and completing his apprenticeship to a shoemaker. In spite of his diminutive size and the dignity of his name, he was mixed up in every street fight, massacre, or tea party that occurred in the Boston of his day.

Even the wealthy John Hancock, who kept careful records of his philanthropy, knew Hewes. According to Forbes, “He [Hancock] called that young scamp, George Robert Twelvetrees Hewes, ‘my lad’ and ‘put his hand into his breeches-pocket and pulled out a crown piece, which he placed softly in his hand.’”

Hewes was present for the Boston Massacre, one of the early events that led to the Tea Party. “George Robert Twelvetrees Hewes, of course, was in the middle of it,” writes Forbes. “He was a little fellow, but ‘stood up straight… and spoke up sharp and quick on all occasions.’ Recently he had married Sally Sumner, a young washerwoman. When Captain Preston and his men shoved their way across King Street, they had bumped smack into Hewes.”

And when it came to the Boston Tea Party, Forbes notes, “No one invited George Robert Twelvetrees Hewes, but no one could have kept him home.” She quotes him as to the size of the raiding party, noting, “Hewes says there were one hundred to a hundred and fifty ‘indians’” that night.

Hewes apparently came to Boston, writes Forbes, through the good graces of America’s first president:

George Robert Twelvetrees Hewes fished nine weeks for the British fleet until he saw his chance [to escape] and took it. Landing in Lynn, he was immediately taken to [George] Washington at Cambridge. The General enjoyed the story of his escape—“he didn’t laugh to be sure but looked amazing good natured, you may depend.” He asked him to dine with him, and Hewes says that “Madam Washington waited upon them at table at dinner-time and was remarkably social.” Hewes was one of the many Boston refugees who never went back there to live. Having served as a privateersman and soldier during the war, he settled outside of the state.

And there, outside the state, was where Hewes lived into his old age, finally telling his story to those who would listen, including S. S. Bliss, who published the little book I found. While Forbes doesn’t list my volume among her bibliography, she does note that George R. T. Hewes was holding young listeners spellbound out in Oswego County, New York, in his old age, and references Peleg W. Chandler’s American Criminal Trials, published in 1841, as a source that “gives what seems to me the most careful analysis of the [Boston] Massacre and I have used this book as my primary source, adding to it various contemporary accounts, especially George Robert Twelvetrees Hewes.”

Reading Hewes’s account, I learned that the Boston Tea Party resembled in many ways the growing modern-day protests against transnational corporations and small-town efforts to protect themselves from chain-store retailers or factory farms. With few exceptions the Tea Party’s participants thought of themselves as protesters against the actions of the multinational East India Company and the government that “unfairly” represented, supported, and served the company while not representing or serving the residents.

Hewes said that many American colonists either boycotted the purchase of tea or were smuggling tea or purchasing smuggled tea to avoid supporting the East India Company’s profits and the British taxes on tea, which, according to Hewes’s account of 1773,

rendered the smuggling of [tea] an object and was frequently practiced, and their resolutions against using it, although observed by many with little fidelity, had greatly diminished the importation into the colonies of this commodity. Meanwhile, an immense quantity of it was accumulated in the warehouses of the East India Company in England. This company petitioned the king to suppress the duty of three pence per pound upon its introduction into America…[10]

That petition was successful and produced the Tea Act of 1773. The result was a boon for the transnational East India Company corporation and a big problem for the entrepreneurial American “smugglers.”

According to Hewes, “The [East India] Company, however, received per- mission to transport tea, free of all duty, from Great Britain to America,” allowing it to wipe out its small competitors and take over the tea business in all of America. “Hence,” he wrote:

it was no longer the small vessels of private merchants, who went to vend tea for their own account in the ports of the colonies, but, on the contrary, ships of an enormous burthen, that transported immense quantities of this commodity, which by the aid of the public authority, might, as they supposed, easily be landed, and amassed in suitable magazines. Accordingly, the company sent its agents at Boston, New York, and Philadelphia, six hundred chests of tea, and a proportionate number to Charleston, and other maritime cities of the American continent. The colonies were now arrived at the decisive moment when they must cast the dye [sic], and determine their course…

Interestingly, Hewes notes that it wasn’t just American small businesses and citizens who objected to the new monopoly powers granted the East India Company by the English Parliament. The company was also putting out of business many smaller tea exporters in England, who had been doing business with American family-owned retail stores for decades, and those companies began a protest in England that was simultaneous with the American protests against transnational corporate bullying and the East India Company’s buying of influence with the British Parliament. Hewes continues:

Even in England individuals were not wanting, who fanned this fire; some from a desire to baffle the government, others from motives of private interest, says the historian of the event, and jealousy at the opportunity offered the East India Company, to make immense profits to their prejudice.

These opposers [sic] of the measure in England [the Tea Act of 1773] wrote therefore to America, encouraging a strenuous resistance. They represented to the colonists that this would prove their last trial, and that if they should triumph now, their liberty was secured forever; but if they should yield, they must bow their necks to the yoke of slavery. The materials were so prepared and disposed that they could easily kindle.

The battle between the small businessmen of America and the huge multinational East India Company actually began in Pennsylvania, according to Hewes. “At Philadelphia,” he writes:

those to whom the teas of the [East India] Company were intended to be con- signed, were induced by persuasion, or constrained by menaces, to promise, on no terms, to accept the proffered consignment.

At New-York, Captain Sears and McDougal, daring and enterprising men, effected a concert of will [against the East India Company], between the smugglers, the merchants, and the sons of liberty [who had all joined forces and in most cases were the same people]. Pamphlets suited to the conjecture, were daily distributed, and nothing was left unattempted by popular leaders, to obtain their purpose.

Resistance was organizing and growing, and the Tea Act was the final straw. The citizens of the colonies were preparing to throw off one of the corporations that for almost two hundred years had determined nearly every aspect of their lives through its economic and political power. They were planning to destroy the goods of the world’s largest multinational corporation, intimidate its employees, and face down the guns of the government that supported it.

A newsletter called The Alarm circulated through the colonies; the May 27, 1773, issue, signed by an enigmatic “Rusticus,”11 made clear the feelings of colonial Americans about England’s largest transnational corporation and its behavior around the world:

Are we in like Manner to be given up to the Disposal of the East India Company, who have now the Assurance, to step forth in Aid of the Minister, to execute his Plan, of enslaving America? Their Conduct in Asia, for some Years past, has given simple Proof, how little they regard the Laws of Nations, the Rights, Liberties, or Lives of Men. They have levied War, excited Rebellions, dethroned lawful Princes, and sacrificed Millions for the Sake of Gain. The Revenues of Mighty Kingdoms have centered in their Coffers. And these not being sufficient to glut their Avarice, they have, by the most unparalleled Bar- barities, Extortions, and Monopolies, stripped the miserable Inhabitants of their Property, and reduced whole Provinces to Indigence and Ruin. Fifteen hundred Thousands, it is said, perished by Famine in one Year, not because the Earth denied its Fruits; but [because] this Company and their Servants engulfed all the Necessaries of Life, and set them at so high a Rate that the poor could not purchase them.

The Pamphleteering Worked

After turning back the company’s ships in Philadelphia and New York, Hewes writes, “In Boston the general voice declared the time was come to face the storm.”

Hewes writes about the sentiment among the colonists who opposed the naked power and wealth of the East India Company and the British government that supported it:

Why do we wait? they exclaimed; soon or late we must engage in conflict with England. Hundreds of years may roll away before the ministers[*] can have perpetrated as many violations of our rights, as they have committed within a few years. The opposition is formed; it is general; it remains for us to seize the occasion. The more we delay the more strength is acquired by the ministers. Now is the time to prove our courage, or be disgraced with our brethren of the other colonies, who have their eyes fixed upon us, and will be prompt in their succor if we show ourselves faithful and firm.

This was the voice of the Bostonians in 1773. The factors who were to be the consignees of the tea, were urged to renounce their agency, but they refused and took refuge in the fortress. A guard was placed on Griffin’s wharf, near where the tea ships were moored. It was agreed that a strict watch should be kept; that if any insult should be offered, the bell should be immediately rung; and some persons always ready to bear intelligence of what might happen, to the neighbouring towns, and to call in the assistance of the country people.

*Hewes refers to the local East India Company employees who doubled as agents of Britain as the “ministers” and their local claim at governance in cooperation with and to the profit of the East India Company as the “ministerial enterprises.”

Rusticus added his voice in the May 1773 pamphlet, saying, “Resolve therefore, nobly resolve, and publish to the World your Resolutions, that no Man will receive the Tea, no Man will let his Stores, or suffer the Vessel that brings it to moor at his Wharf, and that if any Person assists at unloading, landing, or storing it, he shall ever after be deemed an Enemy to his Country, and never be employed by his Fellow Citizens.”[12]

Colonial voices were getting louder and louder about their outrage at the giant corporation’s behavior. Another issue of The Alarm, signed Hampden and dated October 27, 1773, said, “It hath now been proved to you, That the East India Company, obtained the monopoly of that trade by bribery, and corruption. That the power thus obtained they have prostituted to extortion, and other the most cruel and horrible purposes, the Sun ever beheld.”[13]

The People Challenge the Corporation

And then, Hewes says, on a cold November evening, the first of the East India Company’s ships of reduced-tax tea arrived:

On the 28th of November, 1773, the ship Dartmouth with 112 chests arrived; and the next morning after, the following notice was widely circulated.

Friends, Brethren, Countrymen! That worst of plagues, the detested TEA, has arrived in this harbour. The hour of destruction, a manly opposition to the machinations of tyranny, stares you in the face. Every friend to his country, to himself, and to posterity, is now called upon to meet in Faneuil Hall, at nine o’clock, this day, at which time the bells will ring, to make a united and successful resistance to this last, worst, and most destructive measure of administration.

The reaction to the pamphlet—back then one part of what was truly a “free press” in America—was emphatic. Hewes’s account was that, “Things thus appeared to be hastening to a disastrous issue. The people of the country arrived in great numbers, the inhabitants of the town assembled. This assembly which was on the 16th of December, 1773, was the most numerous ever known, there being more than 2,000 from the country present.”

Hewes continues:

This notification brought together a vast concourse of the people of Boston and the neighbouring towns, at the time and place appointed. Then it was resolved that the tea should be returned to the place from whence it came in all events, and no duty paid thereon. The arrival of other cargoes of tea soon after, increased the agitation of the public mind, already wrought up to a degree of desperation, and ready to break out into acts of violence, on every trivial occasion of offence….

Finding no measures were likely to be taken, either by the governor, or the commanders, or owners of the ships, to return their cargoes or prevent the landing of them, at 5 o’clock a vote was called for the dissolution of the meet- ing and obtained. But some of the more moderate and judicious members, fearing what might be the consequences, asked for a reconsideration of the vote, offering no other reason, than that they ought to do every thing in their power to send the tea back, according to their previous resolves. This, says the historian of that event,[*] touched the pride of the assembly, and they agreed to remain together one hour.

*Presumably Hewes is referring to himself in the third person, a form considered good manners in the eighteenth century, or this is the voice of the narrator who interviewed him.

The people assembled in Boston at that moment faced the same issue that citizens who oppose combined corporate and co-opted government power all over the world confront today: Should they take on a well-financed and heavily armed opponent when such resistance could lead to their own imprisonment or death? Even worse, what if they lose the struggle, leading to the imposition on them and their children of an even more repressive regime to support the profits of the corporation?

There Are Corporate Spies among Us!

There was a debate late that afternoon in Boston, Hewes notes, but it was short because a man named Josiah Quiney pointed out that some of the people in the group worked directly or indirectly for the East India Company or held loyalty to Britain or both. Quiney suggested that if they took the first step of confronting the East India Company, it would inevitably mean they would have to take on the army of England. He pointed out that they were really dis- cussing the possibility of going to war against England to stop England from enforcing the East India Company’s right to run its “ministerial enterprise” and that some who profited from that enterprise were right there in the room with them.

Hewes goes on to say,

In this conjuncture, Josiah Quiney, a man of great influence in the colony, of a vigorous and cultivated genius, and strenuously opposed to ministerial enterprises, wishing to apprise his fellow-citizens of the importance of the crisis, and direct their attention to probable results which might follow, after demanding silence said, “This ardour and this impetuosity, which are manifested within these walls, are not those that are requisite to conduct us to the object we have in view; these may cool, may abate, may vanish like a flittering shade. Quite other spirits, quite other efforts are essential to our salvation.

“Greatly will he deceive himself, who shall think, that with cries, with exclamations, with popular resolutions, we can hope to triumph in the conflict, and vanquish our inveterate foes. Their malignity is implacable, their thirst for vengeance insatiable. They have their allies, their accomplices, even in the midst of us—even in the bosom of this innocent country; and who is ignorant of the power of those who have conspired our ruin? Who knows not their artifices? Imagine not therefore, that you can bring this controversy to a happy conclusion without the most strenuous, the most arduous, the most terrible conflict; consider attentively the difficulty of the enterprise, and the uncertainty of the issue. Reflict [sic] and ponder, even ponder well, before you embrace the measures, which are to involve this country in the most perilous enterprise the world has witnessed.”

Most Americans today believe that the colonists were upset only because they didn’t have a legislature they had elected that would pass the laws under which they were taxed: “taxation without representation” was their rallying cry. And while that was true, Hewes points out, the thorn in their side, the pin- prick that was really driving their rage, was that England was passing tax laws solely for the benefit of the transnational East India Company at the expense of the average American worker and America’s small-business owners.

Thus “taxation without representation” also meant hitting the average person and small business with taxes while letting the richest and most powerful corporation in the world off the hook for its taxes. It was government sponsorship of one corporation over all competitors, plain and simple.

And the more the colonists resisted the predations of the East India Company and its British protectors, the more reactive and repressive the British government became, arresting American entrepreneurs as smugglers and defending the trade interests of the East India Company.

Among the reasons cited in the 1776 Declaration of Independence for separating America from Britain are, “For cutting off our Trade with all parts of the world: For imposing Taxes on us without our Consent.” The British had used tax and anti-smuggling laws to make it nearly impossible for American small businesses to compete against the huge multinational East India Company, and the Tea Act of 1773 was the final straw.

Thus the group assembled in Boston responded to Josiah Quiney’s comment by calling for a vote. The next paragraph in Hewes’s book says:

The question was then immediately put whether the landing of the tea should be opposed and carried in the affirmative unanimously. Rotch [a local tea seller], to whom the cargo of tea had been consigned, was then requested to demand of the governor to permit to pass the castle [return the ships to England]. The latter answered haughtily, that for the honor of the laws, and from duty towards the king, he could not grant the permit, until the vessel was regularly cleared. A violent commotion immediately ensued; and it is related by one historian of that scene, that a person disguised after the manner of the Indians, who was in the gallery, shouted at this juncture, the cry of war; and that the meeting dissolved in the twinkling of an eye, and the multitude rushed in a mass to Griffin’s wharf.

A First-person Account of the Tea Party

On what happened next, Hewes is quite specific in pointing out that not only were the protesters registering their anger and upset over domination by England and the East India Company but they were willing to commit a million- dollar act of vandalism to make their point. Hewes says:

It was now evening, and I immediately dressed myself in the costume of an Indian, equipped with a small hatchet, which I and my associates denominated the tomahawk, with which, and a club, after having painted my face and hands with coal dust in the shop of a blacksmith, I repaired to Griffin’s wharf, where the ships lay that contained the tea. When I first appeared in the street after being thus disguised, I fell in with many who were dressed, equipped and painted as I was, and who fell in with me and marched in order to the place of our destination.

When we arrived at the wharf, there were three of our number who assumed an authority to direct our operations, to which we readily submitted. They divided us into three parties, for the purpose of boarding the three ships which contained the tea at the same time. The name of him who commanded the division to which I was assigned was Leonard Pitt. The names of the other commanders I never knew.

We were immediately ordered by the respective commanders to board all the ships at the same time, which we promptly obeyed. The commander of the division to which I belonged, as soon as we were on board the ship appointed me boatswain, and ordered me to go to the captain and demand of him the keys to the hatches and a dozen candles. I made the demand accordingly, and the captain promptly replied, and delivered the articles; but requested me at the same time to do no damage to the ship or rigging.

We then were ordered by our commander to open the hatches and take out all the chests of tea and throw them overboard, and we immediately proceeded to execute his orders, first cutting and splitting the chests with our tomahawks, so as thoroughly to expose them to the effects of the water.

In about three hours from the time we went on board, we had thus broken and thrown overboard every tea chest to be found in the ship, while those in the other ships were disposing of the tea in the same way, at the same time. We were surrounded by British armed ships, but no attempt was made to resist us.

We then quietly retired to our several places of residence, without having any conversation with each other, or taking any measures to discover who were our associates; nor do I recollect of our having had the knowledge of the name of a single individual concerned in that affair, except that of Leonard Pitt, the commander of my division, whom I have mentioned. There appeared to be an understanding that each individual should volunteer his services, keep his own secret, and risk the consequence for himself. No disorder took place during that transaction, and it was observed at that time that the stillest night ensued that Boston had enjoyed for many months.

The participants were absolutely committed that none of the East India Company’s tea would ever again be consumed on American shores. Hewes continues:

During the time we were throwing the tea overboard, there were several attempts made by some of the citizens of Boston and its vicinity to carry off small quantities of it for their family use. To effect that object, they would watch their opportunity to snatch up a handful from the deck, where it became plentifully scattered, and put it into their pockets.

One Captain O’Connor, whom I well knew, came on board for that purpose, and when he supposed he was not noticed, filled his pockets, and also the lining of his coat. But I had detected him and gave information to the captain of what he was doing. We were ordered to take him into custody, and just as he was stepping from the vessel, I seized him by the skirt of his coat, and in attempting to pull him back, I tore it off; but, springing forward, by a rapid effort he made his escape. He had, however, to run a gauntlet through the crowd upon the wharf; each one, as he passed, giving him a kick or a stroke.

Another attempt was made to save a little tea from the ruins of the cargo by a tall, aged man who wore a large cocked hat and white wig, which was fashionable at that time. He had slightly slipped a little into his pocket, but being detected, they seized him and, taking his hat and wig from his head, threw them, together with the tea, of which they had emptied his pockets, into the water. In consideration of his advanced age, he was permitted to escape, with now and then a slight kick.

The next morning, after we had cleared the ships of the tea, it was discovered that very considerable quantities of it were floating upon the surface of the water; and to prevent the possibility of any of its being saved for use, a number of small boats were manned by sailors and citizens, who rowed them into those parts of the harbor wherever the tea was visible, and by beating it with oars and paddles so thoroughly drenched it as to render its entire destruction inevitable. In all, the 342 chests of tea—more than ninety thousand pounds— thrown overboard that night were enough to make 24 million cups of tea and were valued by the East India Company at 9,659 pounds sterling or, in today’s U.S. currency, just over $1 million.[14]

In response to the Boston Tea Party, the British Parliament immediately passed the Boston Port Act, stating that the port of Boston would be closed until the citizens of Boston reimbursed the East India Company for the tea they had destroyed. The colonists refused. A year and a half later, the colonists would again openly state their defiance of the East India Company and Great Britain by taking on British troops in an armed conflict at Lexington and Con- cord (“the shots heard ’round the world”) on April 19, 1775.

That war—finally triggered by a transnational corporation and its government patrons trying to deny American colonists a fair and competitive local marketplace—would last until 1783.