Sunday Excerpt: Unequal Protection - The Deciding Moment?

How Corporations Became 'People' - and How You Can Fight Back

Back in 2002, when I wrote this book, most Americans thought the Boston Tea Party was a revolt against “excess taxes” and that “corporate personhood” was something the Supreme Court conferred on companies back in 1886. This book blew up both myths, pointing out that the Boston Tea Party was a revolt against the British government giving the East India Company the largest corporate tax cut in history (so they could unfairly compete with small colonial tea merchants) — basically a revolt against the Wal-Mart-ization of the colonies — and that the Supreme Court did not rule that corporations are persons and thus entitled to rights under the Bill of Rights in 1886 (it was a corrupt scam by a bribed SCOTUS justice and Court Clerk). In the 20 years since Unequal Protection first came out, this “new” knowledge is now widespread. With permission from the publisher, Berrett-Koehler, I’ll be sharing most of the book (the updated edition) with you, one chapter at a time (and not always in order), over the next dozen or so Sundays.

The Deciding Moment?

Part of the American Revolution was about to be lost a century after it had been fought. At the time probably very few of the people involved realized that what they were about to witness could be a counterrevolution that would change life in the United States and, ultimately, the world over the course of the following century.

In 1886 the Supreme Court met in the U.S. Capitol building, in what is now called the Old Senate Chamber. It was May, and while the northeastern states were slowly recovering from the most devastating ice storm of the century just three months earlier, Washington, D.C., was warm and in bloom.

In the Supreme Court’s chamber, a gilt eagle stretched its 6-foot wingspan over the head of Chief Justice Morrison Remick Waite as he glared down at the attorneys for the Southern Pacific Railroad and the county of Santa Clara, California. Waite was about to pronounce judgment in a case that had been argued over a year earlier, at the end of January 1885.

The chief justice had a square head with a wide slash of a mouth over a broomlike shock of bristly graying beard that shot out in every direction. A graduate of Yale University and formerly a lawyer out of Toledo, Ohio, Waite had specialized in defending railroads and large corporations.

In 1846 Waite had run for Congress as a Whig from Ohio but lost before being elected as a state representative in 1849. After serving a single term, he had gone back to litigation on behalf of the biggest and wealthiest clients he could find, this time joining the Geneva Arbitration case suing the British government for helping outfit the Confederate Army with the warship Alabama. He and his delegation won an astounding $15.5 million (close to $200 billion in today’s dollars) for the United States in 1871, bringing him national attention in what was often referred to as the Alabama Claims case.

In 1874, when Supreme Court Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase died, President Ulysses S. Grant had real trouble selecting a replacement, in part because his administration was embroiled in a railroad bribery scandal. His first two choices withdrew, his third was so patently political that it was certain to be rejected by the Senate, and three others similarly failed to pass muster. On his seventh try, Grant nominated attorney Waite.

Waite had never before been a judge in any court, but he passed Senate confirmation, instantly becoming the most powerful judge in the most powerful court in the land. It was a position and a power he relished and promoted, even turning down the 1876 Republican nomination for president to stay on the Court and to serve as a member of the Yale [University].

Standing before Waite and the other justices of the Supreme Court that spring day were three attorneys each for the railroad and the county.

The chief legal adviser for the Southern Pacific Railroad was S.W. Sanderson, a former judge. He was a huge, aristocratic bear of a man, more than 6 feet tall, with neatly combed gray hair and an elegantly trimmed white goatee. For more than two decades, Sanderson had made himself rich, litigating for the nation’s largest railroads. Artist Thomas Hill included a portentous and dignified Sanderson in his famous painting The Last Spike about the 1869 transcontinental meeting of the rail lines of the Union Pacific and Central Pacific railroads at Promontory Summit, Utah.

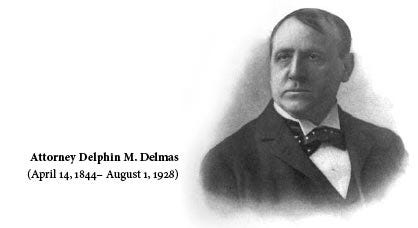

The lead lawyer for Santa Clara County was Delphin M. Delmas, a Democrat who later went into politics and by 1904 was known as “the Silver tongued Orator of the West” when he was elected a delegate from California to the Democratic National Convention. Whereas Waite and Sanderson had spent their lives serving the richest men in America, Delmas had always worked on behalf of local California governments and, later, as a criminal defense attorney. For example, he passionately and single-handedly argued pro bono before the California legislature for a law to protect the nation’s last remaining redwood forests.

Fiercely defensive about “the rights of natural persons,” Delmas was a fastidious, unimposing man, known to wear “a frock coat, gray-striped trousers, a wing collar and an Ascot tie,” whose “voice thrummed with emotion,” and he was nationally known as the master dramatist of America’s courtrooms. He had a substantial nose and a broad forehead only slightly covered in its center with a wispy bit of thinning hair. In the courtroom he was a brilliant lawyer, as the nation would learn in 1908 when he successfully defended Harry K. Thaw for murder in what was the most sensational case of the first half of the century, later made into the 1955 movie The Girl in the Red Velvet Swing, starring Ray Milland and Joan Collins (Delmas was played by Luther Adler).

The case about to be decided in the Old Senate Chamber before Justice Waite’s Supreme Court was about the way Santa Clara County had been taxing the land and rights-of-way owned by the Southern Pacific Railroad. Claiming the taxation was improper, the railroad had refused for six years to pay any taxes levied by Santa Clara County, and the case had ended up before the Supreme Court, with Delmas and Sanderson making the main arguments.

Although the case on its face was a simple tax matter, having nothing to do with due process or human rights or corporate personhood, the attorneys for the railroad nonetheless used much of their argument time to press the issue that the railroad corporation was, in fact, a “person” and should be entitled to the same right of equal protection under the law that was granted to former slaves by the Fourteenth Amendment.

The Mystery of 1886 and Chief Justice Waite

In the decade leading up to this May day in 1886, the railroads had lost every Supreme Court case that they had brought seeking Fourteenth Amendment rights. I’ve searched dozens of histories of the time, representing a wide variety of viewpoints and opinions, but only two have made a serious attempt to answer the question of what happened that fateful day—and their theories clash.

No laws were passed by Congress granting corporations the same treatment under the Constitution as living, breathing human beings, and none has been passed since then. It was not a concept drawn from older English law. No court decisions, state or federal, held that corporations were or should be considered the same as natural persons instead of artificial persons. The Supreme Court did not rule, in this or any other case, on the issue of corporate personhood.

In fact, to this day there has been no Supreme Court ruling that explicitly explains why a corporation—with its ability to continue operating forever, its being merely a legal agreement that can’t be put in jail and doesn’t need fresh water to drink or clean air to breathe—should be granted the same constitutional rights our Founders fought for, died for, and granted to the very mortal human beings who are citizens of the United States, to protect them against the perils of imprisonment and suppression they had experienced under a despot king.

But something happened in 1886, even though nobody to this day knows

exactly what or why.

That year Sanderson decided to again defy a government agency that

was trying to regulate his railroad’s activity. This time he went after Santa Clara County, California. His claim, in part, was that because a railroad corporation was a “person” under the Constitution, local governments couldn’t discriminate against it by having different laws and taxes in different places. It was a variation on the Fourteenth Amendment argument made by civil rights advocates in the 1960s that if a White man could sit at a Woolworth’s lunch counter, a Black man should receive the same privilege. In 1885 the case came before the Supreme Court.

In arguments before the Court in January 1885, Sanderson asserted that corporate persons should be treated the same as natural (or human) persons. He said, “I believe that the clause [of the Fourteenth Amendment] in relation to equal protection means the same thing as the plain and simple yet sublime words found in our Declaration of Independence, ‘all men are created equal.’ Not equal in physical or mental power, not equal in fortune or social position, but equal before the law.”1

Sanderson’s fellow lawyer for the railroads, George F. Edmunds, added his opinion that the Fourteenth Amendment leveled the field between artificial persons (corporations) and natural persons (humans) by a “broad and catholic provision for universal security, resting upon citizenship as it regarded political rights, and resting upon humanity as it regarded private rights.”

But that wasn’t actually what the case was about—that was just a minor point. The county was suing the railroad for back taxes, and the railroad refused to pay, claiming six different defenses. The specifics are not important because the central concern is whether the Court ruled on the Fourteenth Amendment issue. As will be shown below, the Supreme Court’s decision clearly says it did not. But to put the railroad’s complaint in perspective, consider this:

On property with a $30 million mortgage, the railroad was refusing to pay taxes of about $30,000. (That’s like having a $10,000 car and refusing to pay a $10 tax on it—and taking the case to the Supreme Court.)

One of the railroad’s defenses was that when the state assessed the value of the railroad’s property, it accidentally included the value of the fences along the right-of-way. The county, not the state, should have assessed the fences, so the tax being paid in Santa Clara County was different— unequal—from the tax paid in other counties that did their own assessment instead of using the state’s. To make their point (and to make the case a bigger deal), the railroad withheld all its taxes from the county.

All the tax was still due to Santa Clara County; the railroad didn’t dispute that. But it said that the wrong assessor assessed the fences—a tiny fraction of the whole amount—so it refused to pay any of the tax and fought it all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court.

And as it happens, the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) agreed: “the entire assessment is a nullity, upon the ground that the state board of equalization included…property [the fences] which it was without jurisdiction to assess for taxation…”

The Court rejected the county’s appeal, and that was the end of it. Except for one thing. One of the railroad’s six defenses involved the Fourteenth Amendment. As it happens, because the case was decided based on the fence issue, the railroad didn’t need those extra defenses, and the Court never ruled or commented in its ultimate decision on any of them. But one of them— related to the Fourteenth Amendment—still crept into the written record, even though the Court specifically did not rule on it.

Here’s how the matter unfolded. First, the railroad’s defense.

The Treatment That the Railroad Claimed Was Unfair

In the Fourteenth Amendment part of its defense, the railroad said:

That the provisions of the constitution and laws of California…are in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution, in so far as they require the assessment of their property at its full money value, without making deduction, as in the case of railroads [that are only] operated in one county, and of other corporations [that operate in only one county], and of natural persons [who can physically reside in only one county], for the value of the mortgages… [Italics added.]

The italic portions say, in essence, “The state is taxing us in a different way from how it taxes other corporations and real live human beings. That’s not fair, and it violates our corporate right to equal protection that is the same as all other ‘persons’ under the tax laws.”

The implication, of course, is that the state has no right to decide that corporations get different tax rates than humans. And the railroad was using the former slaves’ equal protection clause (the Fourteenth Amendment) as its shield.

The Legal Difference Between Artificial and Natural Persons

In the Supreme Court at that time, cases were typically decided a year after arguments were presented, allowing the justices time to research and prepare their written decisions. So it happened that on January 26, 1885 (a year before the 1886 decision was handed down), Delphin M. Delmas, the attorney for Santa Clara County, made his case before the Supreme Court. I searched for the better part of a year for copies of the arguments made in the case—the Supreme Court kept no notes—and finally discovered, in an antiquarian book shop in San Francisco, a copy of Speeches and Addresses by D. M. Delmas.2 It was a hardbound collection of Delmas’s speeches and his Santa Clara County arguments before the Supreme Court, which he had personally paid to self publish in 1901. It’s incredibly rare to have such a time-machine look back into the past, and—even more exciting—Delmas’s arguments were as brilliant and persuasive as any of the words that Erle Stanley Gardner ever put into the mouth of Perry Mason.

“The defendant claims [that the state’s taxation policy]…violates that portion of the Fourteenth Amendment which provides that no state shall deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws,” Delmas said, standing before the assembled justices while reading from the notes he would later self-publish. He added that such an argument, “if tenable, would place the organic law of California in a position ridiculous to the extreme.”

Winding himself up into full-throated outrage, Delmas rebuked the railroad’s lawyers with a pure and honest fury:

The shield behind which [the Southern Pacific Railroad] attacks the Constitution and laws of California is the Fourteenth Amendment. It argues that the amendment guarantees to every person within the jurisdiction of the State the equal protection of the laws; that a corporation is a person; that, therefore, it must receive the same protection as that accorded to all other persons in like circumstances….

To my mind, the fallacy, if I may be permitted so to term it, of the argument lies in the assumption that corporations are entitled to be governed by the laws that are applicable to natural persons. That, it is said, results from the fact that corporations are [artificial] persons, and that the last clause of the Fourteenth Amendment refers to all persons without distinction.

This was the crux of the argument that the railroad had been putting forth and on which, in the Ninth Circuit Court in California, Judge Stephen J. Field had kept ruling. Because the Fourteenth Amendment says no “person” can be denied equal protection under the law, and corporations had been considered a type of person (albeit an artificial person) for several hundred years under British common law, the railroad was now trying to get that recognition under American constitutional law.

Delmas said: “The defendant has been at pains to show that corporations are persons, and that being such they are entitled to the protection of the Fourteenth Amendment….The question is, Does that amendment place corporations on a footing of equality with individuals?”

He then quoted from the bible of legal scholars—the book that the Framers of our Constitution had frequently cited and referenced in their deliberations in 1787 in Philadelphia—Sir William Blackstone’s 1765 Commentaries on the Laws of England: “Blackstone says, ‘Persons are divided by the law into either natural persons or artificial. Natural persons are such as the God of nature formed us; artificial are such as are created and devised by human laws for the purposes of society and government, which are called corporations or bodies politic.'”3

Delmas then moved from quoting the core authority on law to pleading common sense. If a corporation was a “person” legally, why couldn’t it make out a will or get married, for example?

This definition suggests at once that it would seem unnecessary to dwell upon, that though a corporation is a person, it is not the same kind of person as a human being, and need not of necessity—nay, in the very nature of things, cannot—enjoy all the rights of such or be governed by the same laws. When the law says, “Any person being of sound mind and of the age of discretion may make a will,” or “any person having arrived at the age of majority may marry,” I presume the most ardent advocate of equality of protection would hardly contend that corporations must enjoy the right of testamentary disposition or of contracting matrimony.

It’s about real human people, Delmas said. Any idiot who looked at the history or purpose of the Fourteenth Amendment could figure that out: “The whole history of the Fourteenth Amendment demonstrates beyond dispute that its whole scope and object was to establish equality between men—an attainable result—and not to establish equality between natural and artificial beings—an impossible result.”

As a good liberal California Democrat (as distinct from the southern Democrats), Delmas was furious. He’d spent much of his life fighting for the little guy, agreed strongly with the Radical Republicans (who had mostly become Democrats a decade earlier) about civil rights, and knew—as did anybody who read the newspapers of that era—the history of the Fourteenth Amendment.

The railroad lawyer Sanderson had before made a claim that a “secret committee” of Congress that helped write the Fourteenth Amendment had meant for it to equalize corporate persons and human persons. Delmas, if his performance before the Supreme Court was consistent with his later well documented performances in criminal courtrooms, would have been trembling in righteous indignation as he said that the Fourteenth Amendment “is as broad as humanity itself “:

Wherever man is found within the confines of this Union, whatever his race, religion, or color, be he Caucasian, African, or Mongolian, be he Christian, infidel, or idolater, be he white, black, or copper-colored, he may take shelter under this great law as under a shield against individual oppression in any form, individual injustice in any shape. It is a protection to all men because they are men, members of the same great family, children of the same omnipotent Creator.

In its comprehensive words I find written by the hand of a nation of sixty millions in the firmament of imperishable law the sentiment uttered more than a hundred years ago by the philosopher of Geneva, and re-echoed in this country by the authors of the Declaration of the Thirteen Colonies: Proclaim to the world the equality of man.

Speaking of the “object of the Fourteenth Amendment,” Delmas said it straight out:

Its mission was to raise the humble, the down-trodden, and the oppressed to the level of the most exalted upon the broad plain of humanity—to make man the equal of man; but not to make the creature of the State—the bodiless, soulless, and mystic creature called a corporation—the equal of the creature of God….

Therefore, I venture to repeat that the Fourteenth Amendment does not command equality between human beings and corporations…

In closing his argument, Delmas had to add a punctuation mark. This could be, he suggested, one of the most important Supreme Court cases in the history of the United States because if corporations were given the powerful cudgel of human rights secured by the Bill of Rights, their ability to amass wealth and power could lead to death, war, and the impoverishment of actual human beings on a massive scale.

“I have now done,” he said. “Yet I cannot but think that the controversy now debated before your Honors is one of no ordinary importance.”

A year and five months passed while the Supreme Court debated the issues in private. And then came the afternoon of May 10, 1886, the fateful moment for the fateful words of the Court, upon which hung much of the future of the United States and, later, much of the world.

Chief Justice Waite Rewrites the Constitution (or Does He?)

According to the record left to us, here’s what seems to have happened. For reasons that were never recorded, moments before the Supreme Court was to render its decision in the now-infamous Santa Clara County v. Southern Pacific Railroad case, Chief Justice Waite turned his attention to Delmas and the other attorneys present.

As railroad attorney Sanderson and his two colleagues watched, Waite told Delmas and his two colleagues, “The court does not wish to hear argument on the question whether the provision in the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution, which forbids a state to deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws, applies to these corporations. We are of the opinion that it does.” He then turned to Justice John M. Harlan, who delivered the Court’s opinion.

In the written record of the case, the court reporter noted, “The defendant corporations are persons within the intent of the clause in section 1 of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States, which forbids a State to deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”

This written statement, that corporations were persons rather than artificial persons, with an equal footing under the Bill of Rights as humans, was not a formal ruling of the court but was reportedly a simple statement by its chief justice, recorded by the court reporter.

There was no Supreme Court decision to the effect that corporations are equal to natural persons and not artificial persons. There were no opinions issued to that effect and therefore no dissenting opinions on this immensely important constitutional issue.

The written record, as excerpted above, simply assumed corporate personhood without any explanation why. The only explanation provided was the court reporter’s reference to something he says Waite said, which essentially says, “that’s just our opinion” without providing legal argument.

In these two sentences (according to the conventional wisdom), Waite weakened the kind of democratic republic the original authors of the Constitution had envisioned, and he set the stage for the future worldwide damage of our environmental, governmental, and cultural commons. The plutocracy that had arisen with the East India Company in 1600 and had been fought back by America’s Founders had gained a tool that was to allow it, in the coming decades, to once again gain control of most of North America and then the world.

Ironically, of the 307 Fourteenth Amendment cases brought before the Supreme Court in the years between Waite’s proclamation and 1910, only 19 dealt with African Americans: 288 were suits brought by corporations seeking the rights of natural persons.

Supreme Court Justice Hugo Black pointed out fifty years later, “I do not believe the word ‘person’ in the Fourteenth Amendment includes corporations…. Neither the history nor the language of the Fourteenth Amendment justifies the belief that corporations are included within its protection.”4

Sixty years later Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas made the same point, writing, “There was no history, logic or reason given to support that view [that corporations are legally ‘persons’].”5

There was no change in legislation, and then-president Grover Cleveland had not issued a proclamation that corporations should be considered the same as natural persons. To the contrary President Cleveland, the only Democrat to serve as president during the Robber Baron Era, in his December 3, 1888, State of the Union address, said,

The gulf between employers and the employed is constantly widening, and classes are rapidly forming, one comprising the very rich and powerful, while in another are found the toiling poor. As we view the achievements of aggregated capital, we discover the existence of trusts, combinations, and monopolies, while the citizen is struggling far in the rear or is trampled to death beneath an iron heel. Corporations, which should be the carefully restrained creatures of the law and the servants of the people, are fast becoming the people’s masters.6

The U.S. Constitution does not even contain the word corporation and has never been amended to contain it because the Founders wanted corporations to be regulated as close to home as possible, by the states, so they could be kept on a short leash—presumably so nothing like the East India Company would ever again arise to threaten the entrepreneurs of America.

But as a result of this case, for the past one hundred–plus years corporate lawyers and politicians have claimed that Chief Justice Waite turned the law on its side and reinvented America’s social hierarchy.

“But wait a minute,” many legal scholars have said over the years. Why would Waite say, before arguments about corporations being persons, that the court had already decided the issue—and then allow Delmas and Sanderson to argue the point anyway? Alternatively, why would he say such a thing after arguments had already been made? By all accounts Waite was a rational and capable justice, so it wouldn’t make sense that he would do either of those things.

Several theories have been advanced about what really happened. But first, let’s look at what the Supreme Court decision actually said in the 1886 Santa Clara case.

What the Court Actually Said About Personhood

The Supreme Court generally tries to stay out of a fight. If a case can be thrown out or decided on simpler grounds, there’s no need to complicate things by issuing a new decision. And in this case, the Court’s decision specifically mentioned this: “These questions [regarding the constitutional amendment] belong to a class which this court should not decide unless their determination is essential to the disposal of the case…” (Italics added.)

It continued, saying that the question of “unless it is essential to the case” depended on how strong the other defenses were. “Whether the present cases require a decision of them depends upon the soundness of another proposition, upon which the court…in view of its conclusions upon other issues, did not deem it necessary to pass.” In other words, because of other issues (who should assess the fences), the Court wasn’t even going to consider whether to rule on the Fourteenth Amendment issue of corporate personhood.

The decision then identifies the fence issue and concludes that there’s nothing left to decide because they’re basing their ruling entirely on California law and the California Constitution. “If these positions are tenable, there will be no occasion to consider the grave questions of constitutional law upon which the case was determined…as the judgment can be sustained upon this ground, it is not necessary to consider any other questions raised by the pleadings…” So what actually happened? Why have people said, for all these years, that in 1886 the Waite Court in the Santa Clara case decided that corporations were persons under the Fourteenth Amendment? It turns out that the Court said no such thing, and it can’t be found in the ruling.

It Was in the Headnote!

William Rehnquist, then the chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, was seriously irritated. It was April 1978, and the previous November a case had been argued before the Court in which the First National Bank of Boston asserted that, because it was a corporate “person,” it had First Amendment free-speech rights with regard to political speech, that money was the same as speech (since a corporation doesn’t have a mouth but it does have a checking account), and that therefore the laws that the good citizens of Massachusetts had passed to prevent corporations from throwing money around in political or advocacy campaigns should be thrown out.

Rehnquist and his clerks knew what every graduate of an American law school knew—that in 1886 the U.S. Supreme Court had ruled that the Fourteenth Amendment gave corporations the same, or very nearly the same, access to the Bill of Rights as human beings had.

The Court’s majority had written their opinion on First National Bank of Boston v. Bellotti, delivered by Justice Lewis F. Powell and concurred to by Justices Warren Burger, Potter Stewart, Harry Blackmun, and John Paul Stevens. It opened with a quick summary of the issues:7

Appellants, national banking associations and business corporations, wanted to spend money to publicize their views opposing a referendum proposal to amend the Massachusetts Constitution to authorize the legislature to enact a graduated personal income tax.

They brought this action challenging the constitutionality of a Massachusetts criminal statute that prohibited them and other specified business corporations from making contributions or expenditures “for the purpose of…influencing or affecting the vote on any question submitted to the voters, other than one materially affecting any of the property, business or assets of the corporation.

The majority opinion then cut right to the chase: “The portion of the Massachusetts statute at issue violates the First Amendment as made applicable to the States by the Fourteenth.”

Rehnquist, however, was both a curmudgeon and a conservative. In both cases, he believed that the protections from government power offered by the Bill of Rights should extend to only humans (particularly white humans; he had made much of his early career as a Republican partisan in Arizona, challenging the voting status of Blacks and Latinos at the polls from 1958 to 1964.)8

Thus, when the bank argued before the Court—and five Justices agreed with it—that the Massachusetts law in question “violates the First Amendment, the Due Process and Equal Protection Clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment,” Rehnquist was off ended, and his tone showed through in his choice of language for his solitary dissent, so provocative that the other dissenting justices did not even join in with it.

He started out by directly challenging his own understanding of Santa Clara:

This Court decided at an early date, with neither argument nor discussion, that a business corporation is a “person” entitled to the protection of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Santa Clara County v. Southern Pacific R. Co., (1886). Likewise, it soon became accepted that the property of a corporation was protected under the Due Process Clause of that same Amendment. See, e.g., Smyth v. Ames, (1898).

But that decision—as Rehnquist noted, made “with neither argument nor discussion” but merely proclaimed by the chief justice from the bench— was wrong, Rehnquist believed. “Early in our history [in 1819],” he wrote,

Mr. Chief Justice Marshall described the status of a corporation in the eyes of federal law: “A corporation is an artificial being, invisible, intangible, and existing only in contemplation of law. Being the mere creature of law, it possesses only those properties which the charter of creation confers upon it, either expressly, or as incidental to its very existence. These are such as are supposed best calculated to effect the object for which it was created.”

Restating that concept in his own words, Rehnquist continued in his dissent:

It might reasonably be concluded that those properties, so beneficial in the economic sphere, pose special dangers in the political sphere.

Furthermore, it might be argued that liberties of political expression are not at all necessary to effectuate the purposes for which States permit commercial corporations to exist. So long as the Judicial Branches of the State and Federal Governments remain open to protect the corporation’s interest in its property, it has no need, though it may have the desire, to petition the political branches for similar protection. Indeed, the States might reasonably fear that the corporation would use its economic power to obtain further benefits beyond those already bestowed. I would think that any particular form of organization upon which the State confers special privileges or immunities different from those of natural persons would be subject to like regulation, whether the organization is a labor union, a partnership, a trade association, or a corporation….

The free flow of information is in no way diminished by the Commonwealth’s decision to permit the operation of business corporations with limited rights of political expression. All natural persons, who owe their existence to a higher sovereign than the Commonwealth, remain as free as before to engage in political activity.

But Rehnquist had lost. He quoted a fellow justice, Byron White, who also dissented from the ruling, saying,

The interest of Massachusetts and the many other States which have restricted corporate political activity…is not one of equalizing the resources of opposing candidates or opposing positions, but rather of preventing institutions which have been permitted to amass wealth as a result of special advantages extended by the State for certain economic purposes from using that wealth to acquire an unfair advantage in the political process….

And then he turned to other matters. There were other cases to decide. The bank had won.

How We All Got It Wrong

Chief Justice Rehnquist was laboring under a misconception that was quite common over the past hundred years. In 2003, when the first edition of this book came out, I was invited to address about two hundred students and faculty at a New England law school. I asked for a show of hands “among those of you who know that in 1886 in the Santa Clara County versus Southern Pacific Railroad case, the U.S. Supreme Court declared that corporations were entitled to constitutional rights?” Every hand in the room went up. (And then they got an earful.)

When I first began research for this book, I read a lot of histories of America and commentaries on corporate power. Many referenced this 1886 case, and all said that the Supreme Court ruled in that case that corporations should get the same protections under the Constitution as do human beings. In 1993 Richard L. Grossman and Frank T. Adams wrote, in Taking Care of Business:9

Another blow to citizen constitutional authority came in 1886. The Supreme Court ruled in Santa Clara County v. Southern Pacific Railroad that a private corporation was a natural person under the U.S. Constitution, sheltered by the Bill of Rights and the 14th Amendment.

“There was no history, logic or reason given to support that view,” Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas was to write sixty years later.

But the Supreme Court had spoken. Using the 14th Amendment, which had been added to the Constitution to protect freed slaves, the justices struck down hundreds more local, state and federal laws enacted to protect people from corporate harms. The high court ruled that elected legislators had been taking corporate property “without due process of law.

David C. Korten, a dear friend, one of the smartest guys on the planet on these topics, and the author of the groundbreaking book When Corporations Rule the World, wrote in 1997, “The idea that corporations should enjoy the rights of flesh and blood persons—including the right of free speech—grew out of a U.S. Supreme Court decision in 1886 that designated corporations as legal persons entitled to all the rights and protections afforded by the Bill of Rights of the U.S. Constitution.”

Even www.encyclopedia.com still, in 2010, says:

Q. When did the Supreme Court hold that corporations were persons?

A. In 1886, the Supreme Court held that corporations were “persons” for the purposes of constitutional protections, such as equal protection.

When I began writing this book, I was operating on the assumption that Justices Douglas and Rehnquist were right and that all the various histories I’d read—histories all the way back to the 1930s—which asserted that the Court had ruled in favor of corporate personhood in the Santa Clara case were right. And as I was finalizing work on the first draft of this book, I decided I probably should read the Santa Clara case in its original version.

At the time (2002), I lived just a few blocks from the Vermont state capitol complex and knew that that state had an old and very, very far-reaching law library. When Vermont joined the Union in 1791, it was already an independent republic (this was true of only Vermont and Texas). It issued its own coins and had its own legislature and constitution. It had its own capitol building and its own Supreme Court—and its own Supreme Court law library.

So, on a snowy winter day, I bundled up and walked the six blocks from my home to the Vermont Supreme Court building, in search of the original version of the decision that transformed this nation.

In the warmth of the granite block building, librarian Paul Donovan found for me Volume 118 of United States Reports: Cases Adjudged in the Supreme Court at October Term 1885 and October Term 1886, published in New York in 1888 by Banks & Brothers Publishers and written by J. C. Bancroft Davis, the Supreme Court’s reporter.

What I found in the book, however, were two pages of text that are missing from the copies of the decision I could find online on the Supreme Court’s Web site, which is the official version. They were not part of the decision. They weren’t even written by the Supreme Court justices but were a quick summary of- the-case commentary by Davis. He wrote commentaries like these for each case, “adding value” to the published book, from which he earned a royalty.

And there it was, in the notes.

The very first sentence of Davis’s note reads, “The defendant Corporations are persons within the intent of the clause in section 1 of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States, which forbids a State to deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”

That sentence was followed by three paragraphs of small print that summarized the California tax issues of the case. In fact, the notes by Davis, farther down, say,

The main—and almost only—questions discussed by counsel in the elaborate arguments related to the constitutionality of the taxes. This court, in its opinion passed by these questions[italics added], and decided the cases on the questions whether under the constitution and laws of California, the fences on the line of the railroads should have been valued and assessed, if at all, by the local officers, or by the State Board of Equalization…

In other words, the first sentence of “The defendant Corporations are persons…” has nothing to do with the case and wasn’t the issue on which the Supreme Court decided. Two paragraphs later, perhaps in an attempt to explain why he had started his notes with that emphatic statement, Davis remarks:

One of the points made and discussed at length in the brief of counsel for defendants in error was that “Corporations are persons within the meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States.” Before argument Mr. Chief Justice Waite said: “The court does not wish to hear argument on the question whether the provision in the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution, which forbids a State to deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws, applies to these corporations. We are all of the opinion that it does.”

A half-page later, the notes ended and the actual decision, delivered by Justice Harlan, begins—which, as noted earlier, explicitly says that the Supreme Court is not, in this case, ruling on the constitutional question of corporate personhood under the Fourteenth Amendment or any other amendment.

I paid my 70 cents for copies of the pages from the fragile and cracking book and walked down the street to the office of attorney Jim Ritvo, a friend and wise counselor. I showed him what I had found and said, “What does this mean?”

He looked it over and said, “It’s just a headnote.”

“Headnote? What’s a headnote?”

He smiled and leaned back in his chair. “Lawyers are trained to beware of headnotes because they’re not written by judges or justices but are usually put in by a commentator or by the book’s publisher.”

“Are they legal? I mean, are they the law or anything like that?”

“Headnotes don’t have the value of the formal decision,” Jim said. “They’re not law. They’re just a comment by somebody who doesn’t have the power to make or determine or decide law.”

“In other words, this headnote by court reporter J. C. Bancroft Davis, which says that Waite said corporations are persons, is meaningless?”

Jim nodded his head. “Legally, yes. It’s meaningless. It’s not the decision or a part of the decision.”

“But it contradicts what the decision itself says,” I said, probably sounding a bit hysterical.

“In that case,” Jim said, “you’ve found one of those mistakes that so often creep into law books.”

“But other cases have been based on the headnote’s commentary in this case.”

“A mistake compounding a mistake,” Jim said. “But ask a lawyer who knows this kind of law. It’s not my area of specialty.”

So I called Deborah L. Markowitz, Vermont’s secretary of state and one very bright attorney, and described what I had found. She pointed out that even if the decision had been wrongly cited down through the years, it’s now “part of our law, even if there was a mistake.”

I said I understood that (it was dawning on me by then) and that I was hoping to have some remedies for that mistake in my book, but, just out of curiosity, “What is the legal status of headnotes?”

She said, “Headnotes are not precedential,” confirming what Jim Ritvo had told me. They are not the precedent. They are not the law. They’re just a comment with no legal status.

In fact, I later learned that in the years since Santa Clara the Supreme Court has twice explicitly ruled that headnotes in cases have no legal standing whatsoever. The first was United States v. Detroit Timber and Lumber Company (1905), and the second was Burbank v. Ernst (1914). In the Detroit Timber case— in the Court’s official decision and not in its headnote—the majority of the justices concurred that headnotes are “simply the work of the reporter…prepared for the convenience of the profession in the examination of the records.”

So how did it come about that court reporter J. C. Bancroft Davis wrote that corporations are persons in his headnote? And why have one hundred years of American—and now worldwide—law been based on it? Here are the main theories that have been advanced regarding what happened.

The Republican Conspiracy Theory That Empowered FDR

In the early 1930s, the stock market had collapsed and the world was beginning a long and dark slide into the Great Depression and eventually to World War II. Millions were out of work in the United States, and the questions on many people’s minds were Why did this happen? and Who is responsible?

The teetering towers of wealth created by American industrialists during the late 1800s and the early 1900s were largely thought to have contributed to or caused the stock market crash and the ensuing Depression. In less than one hundred years, corporations had gone from being a legal fiction used to establish colleges and trading companies to standing as the single most powerful force in American politics.

Many working people felt that corporations had seized control of the country’s political agenda, capturing senators, representatives, the Supreme Court, and even recent presidents in the magnetic force of their great wealth. Proof of this takeover could be found in the Supreme Court decisions in the years between 1908 and 1914, when the Court, oft en citing corporate personhood, struck down minimum-wage laws, workers’ compensation laws, utility regulation, and child labor laws—every kind of law that a people might institute to protect its citizenry from abuses.

Unions and union members were the victims of violence from private corporate armies and had been declared “criminal conspiracies” by both business leaders and politicians. It seemed that corporations had staged a coup, seizing the lives of American workers—the majority of voters—as well as the elected officials who were supposed to represent them. And this was in direct contradiction of the spirit expressed by the Founders of this country.

It was in this milieu that an American history book first published in 1927, but largely ignored, suddenly became a hot topic. In The Rise of American Civilization, Columbia University history professor Charles A. Beard and women’s suffragist Mary Beard suggested that the rise of corporations on the American landscape was the result of a grand conspiracy that reached from the boardrooms of the nation’s railroads all the way to the Supreme Court.10

They fingered two Republicans: former senator (and railroad lawyer) Roscoe Conkling and former congressman (and railroad lawyer) John A. Bingham. The theory, in short, was that Conkling, when he was part of the Senate committee that wrote the Fourteenth Amendment back in 1868, had intentionally inserted the word person instead of the correct legal phrase natural person to describe who would get the protections of the amendment. Bingham similarly worked in the House of Representatives to get the language passed.

Once that time bomb was put into place, Conkling and Bingham left elective office to join in litigating on behalf of the railroads, with the goal of exploding their carefully worded amendment in the face of the Supreme Court.

Thus “Republican lawmakers,” the Beards said, conspired in advance to give full human constitutional rights to corporate legal fictions. “By a few words skillfully chosen,” they wrote, “every act of every state and local government which touched adversely the rights of [corporate] persons and property was made subject to review and liable to annulment by the Supreme Court at Washington.”

This conspiracy theory was widely accepted because the supposed conspirators themselves had said, very publicly, “We did it!” Earlier, in an 1882 case pitting the railroads against San Mateo County, California, Conkling testified (as a paid witness for the railroads) that he had slipped the “person” language into the amendment to ensure that corporations would one day receive the same civil rights Congress was giving to freed slaves. Bingham made similar assertions when appropriate during his turns as a paid witness for the railroads. As a result of these assertions, through the late years of the 1800s both Congressman (and railroad lawyer) were the well-off darlings of the railroads, basking in the light of their successful appropriation of human rights for corporations.

When the Beards’ book was widely read in the early 1930s, it gave names and faces to the villains who had turned control of America over to what were then called the Robber Barons of industry. Conkling, Bingham, and Justice Waite were all dead by the time of the Great Depression, and all were judged guilty by the American public of pulling off the biggest con in the history of the republic.

The firestorm of indignation that swept the country helped set the stage for Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, using legislative means and packing the Supreme Court to turn back the corporate takeover—at least in part—and returning to average working citizens some of the rights and the benefits they felt had been stolen from them in 1886.

It was widely accepted that Conkling and Bingham had pulled off this trick successfully—purposefully using person instead of natural person or citizen when they helped write the Fourteenth Amendment—and corporate personhood was a fait accompli. It was done, and it couldn’t be undone. Confronted with the reality of the language of the Fourteenth Amendment, the Supreme Court had been forced to recognize that corporations were persons under the U.S. Constitution because of the precedent of the 1886 Santa Clara case.

Senator Henry Cabot Lodge apparently ratified the coup on January 8, 1915, when he unwittingly promulgated Conkling’s myth in a speech to the Senate about the 1882 San Mateo case:

In the case of San Mateo County against Southern Pacific Railroad, Mr. Conkling introduced in his arguments excerpts from the Journal [of the Senate committee writing the Fourteenth Amendment], then unprinted, to show that the Fourteenth Amendment did not apply solely to Negroes, but applied to persons, real and artificial of any kind. It was owing to this, undoubtedly, that the [Supreme] Court extended it to corporations.

The journal Lodge referenced is the secret journal that never existed. Nonetheless, it was a done deal, conventional wisdom suggested, and the Supreme Court had been forced to acknowledge the reality of corporate personhood —or, some suggested, had gone along with it because Waite and the other justices were corrupt stooges of the railroads but wielded the majority vote. In either case, it had been the intent of at least some of the legislators who draft ed the Fourteenth Amendment (Conkling and Bingham) that corporations should have the constitutional rights of natural persons.

The Republican Conspiracy Theory Collapses

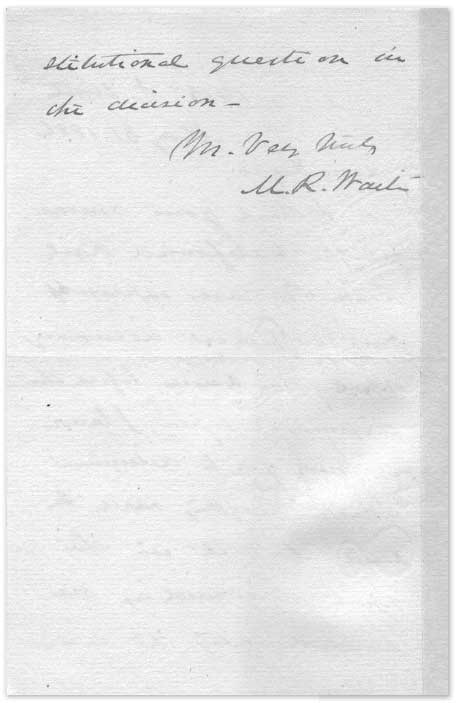

In the 1960s author, attorney, and legal historian Howard Jay Graham came across a previously unexamined treasure in the personal papers of Chief Justice Waite, which had been gathering dust at the Library of Congress.

In Waite’s private correspondence with J. C. Bancroft Davis (his former recorder of the Court’s decisions), Graham made a startling discovery: the entire thing had been a mistake.

What had vexed legal authorities for nearly eighty years was why Waite would say, “The Court does not wish to hear argument…” when the arguments were already finished. Further, why wasn’t there any discussion of this explosive new doctrine of corporate personhood in the Court’s ruling or in its dissents? It was as if they said it and then forgot they had said it. Complicating the situation further, if the Court had arrived at a huge constitutional decision with sweeping implications, why did the decision say it was based on a technicality about fences? It just didn’t seem to add up.

Looking over Justice Waite’s personal papers, Graham found a note from Davis to Waite. At one point in the arguments, Waite had apparently told railroad lawyer Sanderson to get beyond his arguments that corporations are persons and get to the point of the case. Court reporter Davis, apparently seeking to clarify that, wrote to Waite, “‘In opening, the Court stated that it did not wish to hear argument on the question whether the Fourteenth Amendment applies to such corporations as are parties in these suits. All the judges were of opinion that it does.’

“Please let me know whether I correctly caught your words and oblige.”

Waite wrote back, “I think your mem. in the California Rail Road Tax cases expresses with sufficient accuracy what was said before the argument began. I leave it with you to determine whether anything need be said about it in the report inasmuch as we avoided meeting the constitutional question in the decision.” (Italics added.)

With thanks to Michael Kinder, who found this in the J. C. Bancroft Davis collection of personal papers in the National Archives in Washington, D.C., where they had been sitting, largely unnoticed, for almost a century, the actual letters are reproduced on the following pages.

Graham notes in an article first published in the Vanderbilt Law Review that Waite explicitly pointed out to court reporter Davis that the constitutional question of corporate personhood was not included in their decision. According to Graham, Waite was instead saying,

something to the effect of, “The Court does not wish to hear further argument on whether the Fourteenth Amendment applies to these corporations. That point was elaborately covered in 1882 [in the San Mateo case], and has been re-covered in your briefs. We all presently are clear enough there. Our doubts run rather to the substance [of the case…the fence issue]. Assume accordingly, as we do, that your clients are persons under the Equal Protection Clause. Take the cases on from there, clarifying the California statutes, the application thereof, and the merits.”

In my opinion, Waite was saying something to the effect of, “Every judge and lawyer knows that corporations are persons of the artificial sort—corporations have historically been referred to as ‘artificial persons,’ and so to the extent that the Fourteenth Amendment covers them, it does so on a corporation- to-corporation basis. But we didn’t rule on the railroad’s claim that corporations should have rights equal to human persons under the Fourteenth Amendment, so I leave it up to you if you’re going to mention the debates or not.”

Another legal scholar and author, C. Peter Magrath, was going through Waite’s papers at the same time as Graham for the biography he published in 1963 titled Morrison R. Waite: Triumph of Character. In his book he notes the above exchange and then says, “In other words, to the Reporter fell the decision which enshrined the declaration in the United States Reports. Had Davis left it out, Santa Clara County v. Southern Pac. R. Co. would have been lost to history among thousands of uninteresting tax cases.”

It was all, at the very best, a mistake by a court reporter. There never was a decision on corporate personhood. “So here at last,” writes Graham, “‘now for then,’ is that long-delayed birth certificate, the reason this seemingly momentous step never was justified by formal opinion.” He adds, in a wry note for a legal scholar, “Think, in this instance too, what the United States might have been spared had events taken a slightly different turn.”

Graham’s Conspiracy Theory

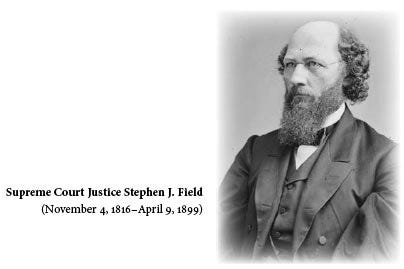

In Everyman’s Constitution, Howard Jay Graham suggests that if there was an error made on the part of court reporter J. C. Bancroft Davis—as the record seems to show was clear—it was probably the result of efforts by Supreme Court Justice Stephen J. Field.11

(November 4, 1816–April 9, 1899)

Field was very much an outsider on the Court and was despised by Waite. As Graham notes,

Field had repeatedly embarrassed Waite and the Court by close association with the Southern Pacific proprietors and by zeal and bias in their behalf. He had thought nothing of pressuring Waite for assignment of opinions in various railroad cases, of placing his friends as counsel for the railroad in upcoming cases, of hinting at times [of actions that] he and they should take, even of passing on to such counsel in the undecided San Mateo case “certain memoranda which had been handed me by two of the Judges.

Field had presidential ambitions and was relying on the railroads to back him. He had publicly announced on several occasions that if he were elected, he would enlarge the size of the Supreme Court to twenty-two so that he could pack it with “able and conservative men.”

Field also thought poorly of Waite, calling him upon his appointment “His Accidency” and “that experiment” of Ulysses Grant. Waite didn’t have the social graces of Field, who was often described as a “popinjay.” And even though Waite had been a lawyer for the railroads, the record appears to show that he did his best to be a truly impartial chief justice during his tenure, eventually literally working himself to death from what was probably congestive heart failure in 1888.

But Field was a grandstander who served on the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals of California at the same time he was a justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. It was often his “corporations are persons” decisions in California cases that led them to reappear before the U.S. Supreme Court—no accident on Field’s part—including the San Mateo case in 1882 and the Santa Clara case in 1886.

And when the justices decided (contrary to what court reporter Davis published months after the decision) that constitutional issues were not involved in Santa Clara County v. Southern Pacific Railroad, Justice Field was incensed.

In his concurring opinion to the Santa Clara case, even though he agreed with the finding that fenceposts should have a different tax rate than railroad land, he was clearly upset that the issue of corporate personhood was not addressed or answered in the case.

Field wrote:

[The court had failed in] its duty to decide the important constitution questions involved, and particularly the one which was so fully considered in the Circuit Court [where Field was also the judge], and elaborately argued here, that in the assessment, upon which the taxes claimed were levied, an unlawful and unjust discrimination was made…and to that extent depriving it [the railroad “person”] of the equal protection of the laws.

At the present day nearly all great enterprises are conducted by corporations… [a] vast portion of the wealth…is in their hands. It is, therefore, of the greatest interest to them whether their property is subject to the same rules of assessment and taxation as like property of natural persons…whether the State… may prescribe rules for the valuation of property for taxation which will vary according as it is held by individuals or by corporations.

The question is of transcendent importance, and it will come here and continue to come until it is authoritatively decided in harmony with the great constitutional amendment (Fourteenth) which insures to every person, whatever his position or association, the equal protection of the laws; and that necessarily implies freedom from the imposition of unequal burdens under the same conditions.

In Everyman’s Constitution Graham documents scores of additional attempts by Supreme Court Justice Field to influence or even suborn the legal process to the benefit of his open patrons, the railroad corporations. Field’s personal letters, revealed nearly a century after his death, show that his motivations, in addition to wealth and fame, were presidential aspirations; he wrote about his hopes that in 1880 and 1888 the railroads would finance his rise to the presidency, which may explain his zeal to please his potential financiers in the 1882 San Mateo case and the 1886 Santa Clara case.

So, this conspiracy theory goes, after the case was decided—without reference to corporations being persons and without anybody on the court except Field agreeing with Sanderson’s railroad arguments that they were persons under the Fourteenth Amendment—Justice Field took it upon himself to make sure the court’s record was slightly revised: it wouldn’t be published until J. C. Bancroft Davis submitted his manuscript of the Court’s proceedings (titled United States Reports) to his publisher, Banks & Brothers in New York, in 1887 and not released until Waite’s death in 1888 or later.

After all, Waite’s comments to reporter Davis were a bit ambiguous— although he was explicit that no constitutional issue had been decided. Nonetheless, court reporter Davis, with his instruction from Waite that Davis himself should “determine whether anything need be said…in the report,” may well have even welcomed the input of Field. And since Field, acting as the judge of the Ninth Circuit in California, had already and repeatedly ruled that corporations were persons under the Fourteenth Amendment, it doesn’t take much imagination to guess that Field would have suggested that Davis include it in the transcript, perhaps even offering the language, curiously matching his own language in previous lower-court cases.

Graham and Magrath, two of the preeminent scholars of the twentieth century (Graham on this issue, and Magrath as Waite’s biographer), both agree that this is the most likely scenario. At the suggestion of Justice Field, almost certainly unknown to Waite, “a few sentences” were inserted into Davis’s final written record “to clarify” the decision. It wasn’t until a year or more later, when Waite was fatally ill, that the lawyers for the railroads safely announced they had seized control of vital rights in the United States Constitution.

The Hartmann Theory

Court reporters had a very different role in the nineteenth century than they do today. It wasn’t until 1913 that the stenograph machine was invented to automate the work of court reporters. Prior to that time, notes were kept in a variety of shorthand forms, both institutionalized and informal. Thus, the memory of the reporter and his (in the nineteenth century, nearly all were men) understanding of the case before him were essential to a clear and informed record being made for posterity.

Being a reporter for the Supreme Court was also not simply a stenographic or recording position. It was a job of high status and high pay. Although the chief justice in 1886 earned $10,500 a year, and the associate justices earned $10,000 per year, the reporter of the Court could expect an income of more than $12,000 per year, between his salary and his royalties from publishing United States Reports. And the status of the job was substantial, as Magrath notes in Waite’s biography: “In those days the reportership was a coveted position, attracting men of public stature who associated as equals with the justices…”

Prior to his appointment to the Court, John Chandler Bancroft Davis was a politically active and ambitious man. A Harvard-educated attorney, Davis held a number of public service and political appointment jobs, ranging from assistant secretary of state for two presidents, to minister to the German Empire, to Court of Claims judge.

This was no ordinary court reporter, in the sense of today’s professionals who do their jobs with clarity and precision but are completely uninvolved in the cases or with the associated parties. He was a political animal, well educated and traveled, and was well connected to the levers of power in his world, which in the 1880s were principally the railroads.

In 1875, while minister to Germany, Davis even took the time to visit Karl Marx, transcribing their conversations in what was considered one of the era’s clearest commentaries about Marx. But Davis also left out part of what Marx said—Davis apparently viewed himself as both reporter and editor. In late 1878 a second reporter tracked down Marx and asked about Davis’s omission. Here is an excerpt from that second article, as it appeared in the January 9, 1879, issue of the Chicago Tribune:

During my visit to Dr. Marx, I alluded to the platform given by J. C. Bancroft Davis in his official report of 1877 as the clearest and most concise exposition of socialism that I had seen. He said it was taken from the report of the socialist reunion at Gotha, Germany, in May 1875. The translation was incorrect, he said, and he [Marx] volunteered correction, which I append as he dictated…

Marx then proceeds to give this second reporter an entire Twelfth Clause about state aid and credit for industrial societies and suggests that Davis had cooperated with Marx in producing a skewed record in recognition of the times and the place where the discussion was held.

I own twelve books written by Davis, which give an insight into the status and the role he held as reporter for the Supreme Court. My frayed, disintegrating copy of Mr. Sumner, the Alabama Claims, and Their Settlement, published in 1878 by Douglas Taylor in New York, is filled with Davis’s personal thoughts and insights on a testimony before Congress.

The book, first published as an article by Davis in the New York Herald on January 4, 1878, says such things as,

Like Mr. Sumner’s speech in April 1869, this remarkable document would have shut the door to all settlement, had it been listened to. To a suggestion that we should negotiate for the settlement of our disputed boundary and of the fisheries, it proposed to answer that we would negotiate only on condition that Great Britain would first abandon the whole subject of the proposed negotiation. I well remember Mr. Fish’s astonishment when he received this document.

Davis summarizes with extensive commentary, such as, “I add to the foregoing narrative that Mr. Motley’s friends were (perhaps not unnaturally) indignant at his removal, and joined him in attributing it to Mr. Sumner’s course toward the St. Domingo Treaty…”

He indirectly references his own time as envoy to Germany when he writes, “They apparently forgot that the more brilliant, the more distinguished, and the more attractive in social life an envoy is, the more dangerous he may be to his country when he breaks loose from his instructions and communicates socially to the world and officially…” As you can see, Davis was fond of flowery writing and thought well of himself.

And then I realized what I was reading. It related to the famous 1871 Geneva Arbitration case, led by attorney Morrison Remick Waite, which won more than $15 million for the U.S. government from England for its help of the Confederate army during the Civil War. Going to another book by Davis (which I had purchased while researching this book), published in 1903 and titled A Chapter in Diplomatic History, I discovered that Davis had been quite active in the Geneva Arbitration case.

During the negotiations with England, he writes:

I answered that I was very sorry at the position of things, but that the difficulty was not of our making; that I would carry his message to Lord Tenterden, but could hold out little hope that he would adopt the suggestion; and that, in my opinion, the Arbitrators should take up the indirect claims and pass upon them while this motion was pending.

That evening I saw Lord Tenterden and told him what had taken place between me and Mr. Adams and the Brazilian arbitrator….About midnight he came to me to say that he had told Sir Roundell Palmer what had passed between him and me, and that Sir Roundell had made a minute of some points which would have to be borne in mind, should the Arbitrators do as suggested. He was not at liberty to communicate these points to me officially; but, if I chose to write them down from his dictation, he would state them. I wrote them down from his dictation, and, early the next morning, convened a meeting of the counsel and laid the whole matter before them.

That Davis was playing more than just the role of a stenographer in this case was indisputable. And the case? It was, again, the Alabama Claims or Geneva Arbitration case, which had made Morrison Remick Waite’s career. Checking the University of Virginia’s law school library, I found the following notes on the Geneva Arbitration case: “The United States’ case was argued by former Assistant Secretary of State Bancroft Davis, along with lawyers Caleb Cushing, William M. Evarts, and Morrison R. Waite, under the direction of Secretary of State Hamilton Fish and Secretary of Treasury George Boutwell.”

Waite and Davis had worked side-by-side on one of the most famous cases in American history (at the time), both in Geneva, Switzerland, and before the U.S. Congress. And all this was a full fifteen years before Davis was to put his pen to his understanding of the Santa Clara County v. Southern Pacific Railroad case when it came before the Supreme Court of which Waite was now chief justice and for which Davis was the head court reporter.

Searching for traces of Davis on the Internet, I found an autograph for sale—it was a letter by President Ulysses Grant, signed by Grant, and also signed by Grant’s acting secretary of state—J. C. Bancroft Davis. (Remember that Grant’s own Republican Party refused to renominate him for the presidency because his administration was so wracked by railroad bribery and corruption scandals.)

Looking through the records of the City of Newburgh, New York, where Davis once lived, I found the Orange County, New York, Directory of 1878–1879, which lists the following note about one of that city’s distinguished citizens. “The Newburgh and New York Railroad Company was organized December 14th, 1864, the road was completed September 1st, 1869. J. C. Bancroft Davis was elected President of the Board of Directors…[on] August 1st, 1868.”

Given his distinguished background and his having worked with railroad tycoons James Taylor and Jay Cooke in the late 1860s, it’s hard to imagine that Davis would insert “corporations are persons” into the record of a Supreme Court proceeding without understanding full well its importance and consequences, even if he was encouraged to do so by Justice Field.

So here is the fourth and final possibility: J. C. Bancroft Davis undertook to rewrite that part of the U.S. Constitution himself, for reasons that to this day are still unknown but probably not inconsistent with his personal political worldview and affiliation with the railroads and that he did it with the encouragement of Field.

Waite was so ill that he missed the entire 1885 session of the Court, was very weak and sick in 1886 and 1887, and died in March 1888. In all probability, he never knew what Davis had written in his name.

Whether it was a simple error by Davis, or Davis was bending to pressure from Field, or Davis simply took it upon himself to use the voice of the Supreme Court to modify the U.S. Constitution—the fact is that an amendment to the Constitution which had been written by and passed in Congress, voted on and ratified by the states, and signed into law by the president, was radically altered in 1886 from the intent of its post–Civil War authors.

And the hand on the pen that did it was that of court reporter J. C. Bancroft Davis, aided and in all probability even persuaded or bought off by the same railroad barons who, through the money and the power of their railroad corporations, owned Justice Stephen J. Field.