Sunday Excerpt: Visiting with an Aboriginal Elder

Glimpses into the life of an extraordinary man

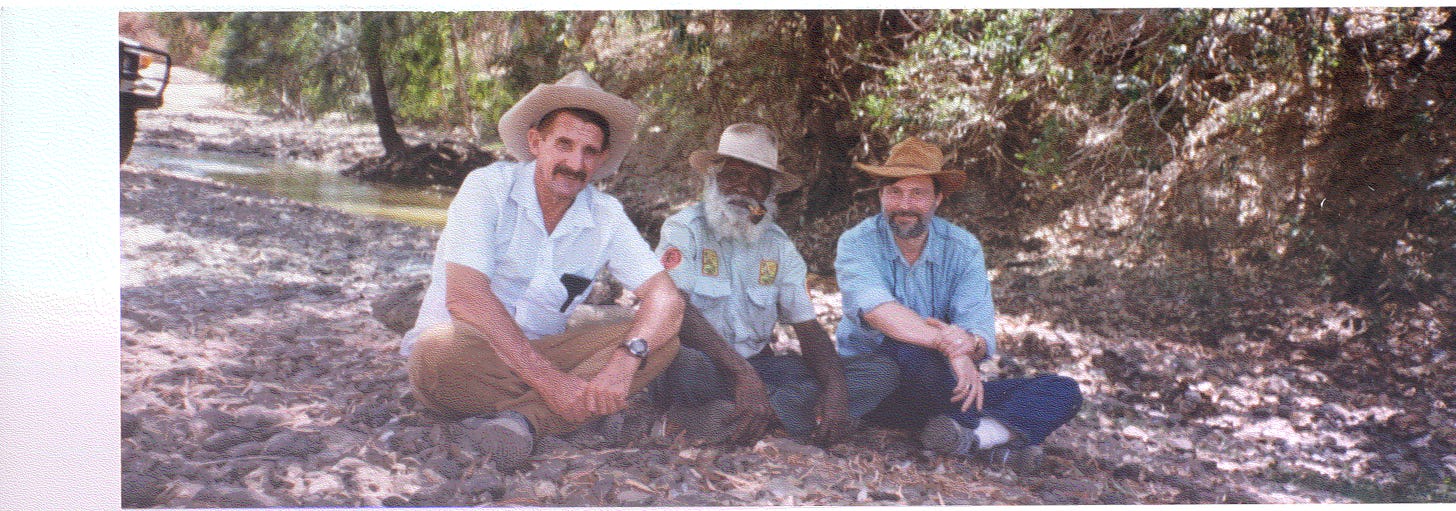

More than two decades ago I spent a fair amount of time over several visits to remote northeastern Australia with Geoff Guest, who was thinking of affiliating his program for Aboriginal children with the German Salem International program I worked with for decades.

Geoff was part Aboriginal, part white and was stolen from his parents at a young age as part of Australia’s program back in the day to “civilize” Aboriginal youth. He was part of the “Stolen Generation” of Aboriginal or mixed-race children taken from their parents by the Australian government between 1910 and 1970.

Recognized as an Aboriginal elder by the 1960s, he married Norma, an Aboriginal woman who became fast friends with Louise and me, and they ran a program for “troubled” Aboriginal youth in the outback for decades. Norma passed away more than a decade ago.

Geoff, who’s now in his 90s, shared some remarkable stories about his life, about the sacred spaces in Australia, about Aboriginal perspectives. Here are a few of the transcripts from our conversations:

Interview with Geoff Guest, an Aboriginal Elder, born 13 Dec 1926, as we traveled together across the remote outback of northern Queensland, August 1998:

My mother was brought up on Branberg creek (later changed to Sherberg) west of Brisbane. Part of the family came from Sherberg — it was a mission and people were sent there — and the main of my family came from the Bowen area. Some of my family were Malay or Afghan and European, and the Aboriginals were from Bowen and sent to Sherberg in 1900’s.

I don’t remember my family — my mother’s — name. I was raised by the Morgans, possibly related, and they took me down south to Wooenbong (the Morgans were Aboriginal) and then to Tablum (when I was age 3 more or less) and then to Lake Tyres in Victoria near Lake’s Entrance (my other two siblings were left in Queensland), and then back to Queensland around 3.

We were constantly moving around to avoid the police, who would steal me because I was a child and they didn’t think Aboriginals should raise children, and also because Mrs. Morgan, who raised me, was looking for her family. Everywhere we went, she had family. She had various men around at various times, but I don’t remember their relationship to her.

When we came back to Queensland, there were police there on horseback and I had to go hide, and the white policemen camped away a bit outside the community. But the two trackers or native police aides they had with them came into our camp. They were having a cup of tea around the fire and one spotted me and grabbed me. Holding me there, he poured a quart pot of hot tea on me and said, “You’re a white kid or too white to be with these fellas!” and he took me away. I can still clearly remember him throwing me over the top of his horse.

The camp was a pole house with bark walls and roof, and pasted newspapers and magazines over the inside walls, bark outside. Termite nest, crushed and watered down, made an excellent hard floor. There was an open fire at end of building that led to a little galley with a chimney made of old roofing iron. The entire building was basically a 12-foot rectangle.

There were two or three other similar buildings, one for each family, each a single room building. This was on the outskirts of a larger white town.

The Aboriginal men folk were allowed to do fencing, yard building, whatever job came along, and the women were put to work as well. If you had a regular job like this, your money had to go into a bank account that was administered by the whites, and if you wanted any of the money, then you had to find a policeman to go to the bank with you to get your money. The policemen usually took a ‘commission’ or the money went into what they called the ‘welfare fund’ which was administered by whites and used to pay the whites’ salaries or for buildings for the whites to use; the Cairns courthouse was paid for by the welfare fund.

The welfare fund was abolished about 30 years ago in the 1960s, but when that happened, the Aboriginals discovered the money they thought they had in the bank had vanished. This led to a few court cases and some publicity. I got very aggressive trying to get our family’s welfare fund money for various aunties and cousins of mine, but I was unsuccessful. They said go to this person then that and it was a huge run-around for a year or so until I gave up.

Anyhow, when I was three and the policeman took me, I was struggling, kicking, and a man I called my grandfather came out with fighting sticks. One of the white police came galloping up and I remember him coming with the gun and being frightened and then my memory is blank. I don’t know if they killed my grandfather or not: I can’t remember. My next memory was late that afternoon, when I got caught because it was the end of the day and I was tired of hiding.

My next memory is the orphanage. We had paper clothes. There were newspapers on the bed as blankets, no sheets, and as a 3-year-old boy, I wore a paper dress made of old newspapers. The orphanage was run by the Anglican church, and had hundreds of children, a big mob. We all slept on the floors. We had no mattresses, just put papers between us and the floor.

In our building it was only boys. I remember we young boys had to be careful of the older boys or you’d be sexually attacked in the bathrooms. I saw boys 6 to 15 being raped: it was a regular thing.

And it wasn’t just the other boys: it was the church-men who ran the orphanage, especially. The worst time was shower time. We had to have a shower in front of the staff once a week, and that was when the staff men raped us.

I wasn’t there a full year because I can’t remember a Christmas. This place was outside of Brisbane. The matrons – the white mission women - were the worst of the lot, they didn’t want sex but were cruel in how they abused the older boys. They had their favorites, and those they hated. They’d be touching their favorite boys, or the boys they disliked had to do housework for the “good” boys. Us little fellas would go to the toilet 12 at a time, or it wasn’t safe.

The women were also the most violent. They beat us with sticks or canes, one had a leather strap on a stick and the strap had studs on it. When you got that, the flesh would fly off you. Toilets were holes in ground or pans, but there was no toilet paper so we had to flush the toilets and then use the 2nd water to wipe yourself with your fingers. Anytime there were visitors, they’d dress us up with woolen shorts that were stiff and rubbed us raw, and they hurt, and they put boots on us, but we looked better. We learned to breathe fast to adjust ourselves to the heat.

Before I came, I still remember the language from where we came, some of the Victorian talk, some of the Woodenbaum talk, the Aboriginal languages, but we’d be flogged if we used them. In this orphanage, we were about 95 percent Aboriginal. After we got up in the morning, we had to hose out the floor we slept on.

Adoption was a euphemism for being given or sold for slave labor — I was adopted when I was around 4 years old. I got adopted quickly because I looked whiter than most of the others. I was adopted by a very old couple who ran a station (the Australian word for what Americans call a ranch).

My first job was to do the fires, two big open fires, at either end of the kitchen. The kitchen was 30-40 feet long with two fires and a tin galley and set back from the building because the building was also bark on the outside and newspaper on the inside.

The man who bought me from the orphanage was an Englishman who ran the station for the owner who lived in a distant big house. I also washed the dishes and scrubbed the rooms, and kept going another fire for rendering the fat that I was responsible for. It made for a lot of wood to gather every day, to make sure the fires were kept going. So I had to get up at 3 a.m. every morning, so the fire would be ready by 4 a.m. As I got older, my chores included feeding the horses and bringing in water. The land had sheep, grain, and cattle. This family mostly did the grain side, the farming side.

I wasn’t allowed to talk inside the house or the yard, and if I did, I got whipped. I still have the whip marks on back from the big flogging I took from the bullwhip when I was 8 years old. I bled badly, could hardly move. After that I lost my ability to talk for a year or two.

The man who adopted me never asked my name or anything else. To him and everybody else on the station, my name was “boy.”

The owner of the station — who lived in the big house a few miles away and employed the man who’d bought me from the orphanage — he called me Geoff, but he wasn’t around to prevent them from hurting me.

The storeroom was at our camp, and I had some responsibility for it as I got older. All the other men working on the camp were white, very racist, very strict. They thought I was white, or mostly white, because my skin was so light, so they just called me ‘boy’ as a joke, not because they thought I was a Murray (Aboriginal). I got on good with them, especially when there was horse-breaking going on.

When swaggers came through and were having hard times — swaggers were white guys going from job to job — I’d sneak them food. Aboriginals couldn’t move around without a permit, so they never showed up.

One swagger showed me how to make chocks to get the wool wagons moving. (They tried to put too much wool on a cart and the horses couldn’t get it moving. Put a block on each wheel, and then 4 men hit it, and it moved. Once it was going, the horses could keep it going.) Later on at our station, the guys were having a problem with the wool wagons, and I said I knew a way to do it and showed them what I’d learned from the swagger. The owner of the place, the boss above the guy who adopted me, was so happy he gave me a baby colt. This was when I was 7 years old. The guy who adopted me tried to sell my colt, but the owner said, “No, it’s the kid’s horse.”

I put the horse into a paddock with the older horses, and ended up with a team of handy horses. Just before that big flogging when I was 8, I’d decided to run away and live in the bush. The first time I ran away, though, I got caught. When you have to walk a long way, you get found easily.

So I started planning it well. I began stealing things from the storehouse, just one thing at a time, a little here and there so it wouldn’t be noticed. There was a bluff with a cave where I used to hide all the stuff, and after about a year I finally had enough to leave, but I was just too afraid to take off. But my mind was made up to keep getting gear. There was a back window where I could drop stuff out. Traps, rifles, poison, poison, clothes, tack.

I was given no education or religion training: I’ve never been in a school. Everyone always said grace. Occasionally a traveling pastor wold come by, but that was only once a year. But the grace didn’t mean anything to the men on the station: it was just what they did.

I discovered I had to learn to think the way a horse thinks, because I was too small to use force. At that time Aboriginals couldn’t come near whites so sometimes I’d see somebody nearby at the next station. They had a cattle place with a second crew that was Aboriginal. They stayed away because they were afraid to talk to any white people. And I had my chores to do, which left me no spare-time to be with them.

It was shearing time a year after the flogging — two Christmases actually, so I was about 10 years old — and the shearers spoke to me, and I tried to say something back.

As soon as I opened my mouth, I saw the Overseer, the man who’d bought me, reaching for his whip, but I grabbed one off the wall with a ball bearing planted in the end of it, and the ball bearing weighed about 2 ounces and as he came to whip me, I pulled back and hit him on the head with it and just saw blood fly everywhere.

To this day, I don’t know if I killed him or not, but I thought I had and that scared me so badly. It wasn’t my plan to hurt him or anybody else, but I had made up my mind that I wasn’t going to get another flogging.

So after I hit him, I ran to the pensioner paddy and got my colt and 5 other horses. The shearers didn’t want to see me get flogged, as they were white Australians and the Overseer was a British bloke, who they all hated. I also moved so quick that nobody stopped me. I was out the door so fast nobody could have caught me, although I think now that they wouldn’t have tried anyway: they knew how he treated me.

I got the horses, went to the cave and got the stuff I’d been stealing and storing, and fled into the bush.

Nobody followed me. It was a rainy day and the shearers won’t shear wet sheep, so we were going to have to put the sheep into a shed and they didn’t do that, I did all that work. On a day like that, they’d just stay inside. It was April. Light rain. Lotsa grass, few trees, black soil country. They probably thought I just went down the road like the time I got caught, and didn’t suspect I had horses and gear ready, so I escaped.

I rode day and night until the horses were exhausted. Two days and nights I rode without stopping, and on the second night the horses were done. I made camp and waited until dark the next day while feeding the horses, and moved off that night again. I had to skirt fences or cut them and patch them back up again. I always repaired the fences I crossed because you don’t want to let stock out, which makes a lot of work for the farmhands, and also it would have left a trail.

Sometimes I’d go a day without feed or water until I had to turn back, sometimes got lost or zigzag around or through the countryside. But I kept moving south-west continually. There was nothing in that direction, it wasn’t built up. The areas to the south, east, and north were more built-up, and so dangerous for me to be seen. I wanted to get into the mountain ranges west of Brisbane.

In Queen Victoria’s Days, they had “the dispersal” but she was condemned for it, although it went on to the 1940s. Landowners would call the Police who’d come to disperse the locals, the Aboriginal people. Shoot them, poison them, or drive them off. They were supposed to just move them, but people resisted leaving their homes, so the police would just shoot them more often than not. Grandfather told story of the police tracking a man he knew down and shooting him in a tree, using dogs to find him. Aboriginal people today fear dogs because the white people taught them to attack the Aboriginal people.

For over 12 months, I worked my way south-west to New South Wales rabbit country. By this time, the flour I’d brought for food was contaminated with weevils. I’d put it in the sun, so they’d leave looking for shade, but they turned the good grain into dust without much nutrition. I’d also run out of salt, and really started craving for it.

I came across this rabbit tracker and asked him if I could trade him something for salt, but he wanted help, so I learned to set rabbit traps and pig out skins. To do this, you put them on a wire frame (pig), turn them inside out and they dry out quick. I stayed a few weeks with him, and finally went with him to a station to get tucker (supplies, flour).

At the station, they were breaking horses at that time and the person doing it to my eye wasn’t very experienced or doing a good job of it. There was this eight- or nine-year-old horse that they’d managed to get a saddle on, but the bloke breaking the horse was frightened of it. It looked to me like he was a bit of an alcoholic, and he was saying he figured they’d have to shoot the horse to get the saddle back off of it. The men around were nodding, and he was getting ready to shoot the horse.

And a couple of the blokes saw me and one said, “What about the young kiddy?” He turned to me. “Can you catch a horse and ride it?” He was just making a joke, you know.

This horse had a big stock saddle with knee pads strapped on him, and he’d already thrown a couple of fellows. Looking closely at the horse, I reckoned he wouldn’t have too much more buck left in him, so I told the men I could catch it and ride it. I was 12 or 13 years old; my birthday, so far as I know, was 13 Dec 1926.

Everyone laughed but I went up and caught the horse without much trouble, took the stirrup off and adjusted it, checked the saddle was right, and when I put them back on I let him have his head — he put a couple of good shakes in and then trotted around and I was on his back.

The manager was impressed and so was the head stockman, as they had quite a few 7-10 year old horses given up on by other breakers, so he offered me ten bob (a bob is a shilling and 10 bob is a half-pound), which was very good money per horse. If I had them shod, got on them, and rode them back into the yard, that was considered a broken horse, plus 10 bob a week wages. I felt confident I could do 4-5 horses a week, and that was big money for me.

The breaker I’d embarrassed got drunk that night and caused a blue (fight) and was fired, so I became the breaker. We did about 20 horses in 4 weeks. It made me feel good — built me up from a frightened kid — although I still had difficulty speaking at that time, from when I’d become a mute after the flogging. But there was a governess at the place teaching school to the manager’s kids, and she taught me to speak. She’d been teaching people to speak who’d been gassed during WWI, she was an old English schoolteacher. Miss Mostrophe was her name, an elderly lady who liked me real good. She’d lost her brothers and boyfriend during WWI and was an ex-Army nurse from WWI. She also taught me to darn socks.

A few months later, a cousin of mine came through with a pack of horses and I went back to Rockhampton with him. He was half-caste. I knew he was my cousin because I recognized his name. I called him “uncle” because he was older, but he was a cousin.

Then I got a job up the other side of Ariba, met a bloke named Ted Carter who’d offered me a job up there, and so I went and took the job.

Around 12, after the job with horses on the station, I went back to my people. There was an entire camp of Murray workers - Aboriginal people - and I stayed there a couple of years. We went up to work at Mallurner for a season, but came back.

The bloke who owned the place, a sandalwood worker named Fred Kepple, and all the families working there then are now called Kepples, too. He brought in fellows from the bush who were still tribal and they took to the horses and cattle — it was a challenge they enjoyed, and they particularly liked the horses. And we learned their ways and stories, how some were forced to carry sandalwood out on their backs, before horses were used. How they used to hide from the Native Police before the turn of the century because the white police were always swapping people about, one land to another, to break up their tribal identity.

They did this so the Aboriginals would help in the “dispersal” work. If they hadn’t lost connection to their people, language, tribe, and clan, they never would have participated, so the white Australians had to break them up, to create a forgetting among them about their own past. Otherwise they wouldn’t go and kill their own families. But the Native Police who were black had so lost their connection that they were able to go to people out of their own district and participate in what they called “dispersing” which often meant killing people, usually shooting them.

On the other hand, because I traveled a lot and kept with my people as often as possible, I learned many different Aboriginal languages and traditions. For example, some different groups have different ideas about the power of womenfolk. Most think they can’t do anything at all, but undoubtedly the women held great power among my Aboriginal people, particularly in the old times.

I learned many stories. For example, at one time it was all dark, all creation. In dreamtime it was all dark, and some talk about the rainbow serpent who we see when we see a rainbow, and he went places and made things. And the animals were named and given names and reasons. And sometimes someone made a mistake and they then had to strike that animal.

Another story is about a girl and boy who were given to each other, and they fell in love and planned to sneak away, but when the family found out they went looking for them, tracking them down. And the boy and girl found a sandy creek and dug a hole in the sand to hide. But all the people threw their spears into the hole, even though you’re supposed to give lawbreakers a chance. So that boy and girl got a chance to live again as the porcupine, because they broke the law but also the people broke the law.

Here’s another: the red ochre veins are the blood of the earth. And so people do things for a reason, even if they didn’t know it. Ochre has a magnetic property, and they’re discovering that.

When whites first came, they thought Aborigines were savage, but they were a very clean people. Only in the last 50 years or so have white people become interested in hygiene. So things change, and perhaps it was hard to get water in those days. It’s easy to criticize people for another culture but sometimes when we look back we find that they made sense.

Many people have different stories, but there are stories people tell about where things happened. Like where a river began, or a cave where people were told to live, and there may be ceremonial signs that were only known to the caretakers there. And there may be a lineage father to sign, or people would look for a special sign for the next caretaker. The signs of caretaker were secret, and so I cannot tell you what they are. We’ll talk about the ones people know about, but not the real secrets.

One is that if somebody goes to a place where a lot of people have been killed, they can unintentionally draw their spirits up through their rectum. One bloke wanted to become clever, a shaman, and he used to walk around calling “eli munji” (sp?) and we went around and when he was calling the spirits we threw a stick on him, but he believed he had the power.

A lot of people believe that they can enter into animals or that they came from animals. This is why if a man’s from the flying fox family, he cannot kill that animal because that’s his group, his totem. It’s the same for kangaroo people, taipan people, and all the rest. Some will believe they have a particular message bird. And I’ve heard many incredible stories about people hearing things from their message birds and I have personally had people tell me something that then happened a few days later — they knew it in advance.

My message bird is called a jerry-jerry or willy wagtail, and I know this is my message bird because around me he doesn’t act in the normal way — he’ll jump in front or get my attention, and then I know it’s a message.

I did that for a while, but then wanted to join the army, as there was a war on, and it seemed like a good opportunity, and I was light enough to pass as white. To join the army, I took the name of a white guy who didn’t want to go to WWII, and joined the army when I was 15 or 16, went in as him.

After a few months, they found out about it and I got arrested by the MPs. I was waiting to go to court with the deserters and drunks and murderers, and an American bloke asked who wanted to get out of jail, and so I volunteered for the American Merchant Marine.

My current wife Norma’s cousin, Peter Aire, was there too, and we joined the merchant marines together. I got on a troop ship and he got put on a Y-class to take the fuel around. He was scared because the boat was just a fiery bomb if it got hit, and he wanted to swap with me because I was on a safer troop ship. So I traded with him, but 3 weeks later he got torpedoed and killed and I made it through.

When we made it back to land, I told them I hated the ocean and was good with horses, so the Americans put me into a pack artillery horse team in India. We got the horses ready from there and landed them in Bombay, and then used them as pack animals to take weapons across India through the northeast. We had to walk 27.5 miles a day — that was the regulation — and I became the Rough Rider — the guy who rode the bucking or misbehaving horses. Normally the officers rode and the enlisted men walked, but often I rode because I could rough ride and help the officers fix their bad horses. We were hauling 75 MM Howitzers, and our packs weighed 75 pounds. My work also included modifying saddles and packs to accommodate infected horses.

Tomorrow we’re going to a Quinken place. There are bad and good Quinken spirits. When you’re there, it’s very bad to call out a person’s name who you’re with, because one of the two Quinkens may follow you back. One is tall and causes mischief, and the other will help you if you’re lost. So if we go there we’ve to be careful about names and not hurt the paintings. This one we’re visiting is a special place. Sometimes they’d paint the things that they wanted to catch to make some magic for that.

We’re breaking all these laws, spoiling all this country, and when we do this, it could bring an end to things.

In the times before the whites arrived, leaders were recognized for their abilities, and held respect. Aboriginal people don’t like bosses — they never had them as such, so it’s difficult to organize things in such a way to get them to work because they never had these ideas of people in charge just because they’re in charge. A group of elders would sit down and come to agreement, but they dislike the idea of one bloke trying to become a boss.

Money counts and the politicians are following the money for power and glory. Many schemes set up for Aboriginal people are designed to fail before they start because, like in white society, they’re trying to get a large number people together. But Aboriginal people traditionally worked with small groups.

The world all over has proven that large groups can’t all work together on the same footing. Even in Aboriginal people, the individual may strive, but the greater hunter will share. The family would work together, but it was also very individualized. We’re led to believe that we can all work together under one big boss or government, but it doesn’t work. That police and guns will solve problems. That force is necessary. We didn’t live that way. For example, hitting someone else’s child that was a huge no-no, it would cause a big blowout, maybe someone could even be killed over it.

Aboriginal children are trained by example, encouraged by example, if somebody did the wrong thing you’d made a joke, make them shame or look small, but never hit or punish. Only by example.

Aboriginal people wouldn’t go into caves because of the spirits there. Books that talk about “Aboriginal caves” are wrong.

Dreamtime is the beginning of time. It’s over. It’s a word for what you call creation, only.

To connect with spirit, we may fast or only eat certain foods — this varies from tribe to tribe. Then we have to smoke ourselves with the smoke from particular plants blown over our bodies. Some groups believe that the leaves from Ironwood tree, for example, chase spirits away.

It may take a week of eating special food and smoking before you go to a special place.

There’s a story of Felix and Saunders who wanted to get clever, so they went to this old lady and asked what to do, and she said you can’t eat porcupine or sugar and you have to go naked and smoke yourself. But the young fellows didn’t believe her so they ate white man’s food. This was in the 1930s. So they went up this mountain and this old lady, fat, painted, climbs up there with them, and they’re laughing at her, then they got to the top and she made the earth tremble and frightened them. And they ran back as fast as they could, and when they got back, they found her sitting in her chair with her dress on, and when they asked her how she got through the prickly pear (brambles) she said she just flew through the air.

The Saunders family down Sherberg way tell this story, people I know, they told me this story themselves. Don’t know which tribe of people, as people came there from everywhere. But they told me this story themselves and it frightened them. They gave up on trying to become clever.

Psychoactive plants.

Pujuri is one, called that way by white people, it’s a very strong plant. Only older fellows know how to process it. You must have gray in your hair before you’re shown how to process the plant.

Then they burn the wattle plant to make the white ash, then that is chewed with the Pujuri, which acts like a catalyst and brings out the alkaloid. It makes people hallucinate, it’s 27 times stronger than nicotine. Used for puberty ceremonies, and to dream something, to get a message, but mostly only the shaman can do that. They’ll take the plant and clap clap-sticks to get dreams. It’s still used in ceremonies, but only a few people know about it. It grows all through the north, and is legal.

Another is corkwood, duboiser is botanical name, which has many psychoactive alkaloids. Around the kingoi district, and around Brisbane, there are some other similar families of plants, but they’re not as strong as those two to my knowledge.

Dreamtime

In the Dreamtime, they say it was all dark and all the animals could talk to one another. And the big bird Broga likes dancing, and called everyone to come and watch him dance. And one day he danced and he said where is the Emu? And they said that the Emu was sitting on her Egg. So he called her stupid and threw the Emu egg up into the sky and it broke and the yolk broke, making the kookaburra laugh. And so the Great Spirit said that was disrespectful, so every morning the Kookaburra must wake up first to laugh when the yolk is broken and the sun rises.

We agree with other indigenous peoples around the world that we humans shouldn’t be destroying the world. Nearly all our people are worried about the fish, the kangaroo, how the wallaby are nearly gone, this rapid change, how bad it is. It’s changing and I think we’ve got to be very careful of overgrazing, clearing too much. While the country will ways trying to go back to what it was, it’s not always possible. Once you clear the trees, it often becomes just desert.

With today’s world population, we’ve got to be concerned about that; when my people took care of this land before the Europeans arrived, there weren’t so many people. Now, if we don’t make some use of something, someone strong will take it from us. Like much of this country has no water to grow vegetables, so they irrigate, pump from the ground — that’s a limited supply. We can’t just be thinking about the next year, we have to think about the next 100 years and more. We have to change the English way of thinking of making every acre as productive as possible. It leaves it so there’s nothing left...and now there is no new land to discover, no new America or Australia to steal from its traditional residents.

First we had the missionaries, who no doubt believed in what they were doing, but they believed everyone should be just like them. The trees were to be pushed down, the native animals killed off, and although many of these people had good hearts, they wanted to convert our people to Europeans and adopt a different agricultural style that is not suited for this land. This made the people very miserable as nothing appeared to be working.

The state government then came along and put in well-trained managers. But there again, they made the same mistakes. And when that was a failure they put local people in charge, but with guidelines so they would try to do the same thing. It was a complete failure again.

Finally, they came up with the idea of having the Aboriginal people work for the dole, so everyone was on equal footing and worked for just enough money to keep alive. The result was that the people who could have been wonderful leaders lost their heart. Of course, this was because no matter how hard they worked, they only got the same pay and recognition as a person doing nothing at all.

The most important privilege a man can have is the privilege to survive. Whether it be hunting and gathering, or earning money at a job, or excelling in a profession or something similar, that sense of accomplishment is important for the nature of a man or woman. History has shown us what has happened in the Communist system. And even though we read how bad it worked and knew about its failures, this appears to be the model they’re now forcing on the Aboriginal communities, to my way of thinking.

Perhaps working for the dole linked to an enterprise where that person could get job satisfaction and personal gains would be a step forward from what we have now. But it makes me cry when you go to a community and everybody is drunk and fighting and next week the money is there no matter what. And no matter what you do, no matter how hard you strive, it doesn’t matter.

We’ve had missionaries fail, the state government fail, they’re also asking local people to take over, but forcing us into the same model. The local people face the difficulty in some cases of limited education and expertise in the business world. This is breaking a lot of people’s hearts because they take personally the criticism — and reality — of things not working in the Aboriginal communities. Perhaps we should be looking at why they didn’t work originally and come up with a model better suited than the one we’re using at the present.

The Aboriginal people must have respect for their land and culture, but also respect for their own. Sixty people trying to run an enterprise — all bosses and no workers — is doomed to failure.

Plus we have the land problem. People want to lease that land themselves from their own community, then sell it at a profit to a community member, or if not lease it to a complete outsider, and that will keep the value of their land up. But that land can never be owned, it can only be leased by the Aboriginal council as such.

In most Aboriginal communities you’ll find somebody who gets most of the grant money and has boats and cars and they’ve adopted European values. They’re on the council set up by the white people and they think they’re going to have an easier life because they’ve gone the white’s way. But I think we should take what’s appropriate today and leave behind what’s no longer useful.

We’ve gotta recognize that culture changes, and always keep an eye out for what’s good for the future. If corporations, governments, or whatever have an opportunity to take over, they will. We live in a culture now of power and greed. This is not right. It can’t last.

Now we’re fighting to get back the land that was ours 100 years ago, and that’s not right that we should have to fight to get back what was stolen. We can’t look away and pretend the world isn’t changing, but I know it’s changing fast. It’s changed. But if we set things in place now to protect the environment and perhaps only lightly graze it, for example, maybe we can save it. For example, I believe we should have limited access to our swamps and lands. Wild pigs, brought here from Europe, are doing incredible damage to the land: there’s been so much disruption of the natural world by the things whites have brought to this land.

Aboriginal people get enjoyment out of working cattle and horses. We need more programs for them, especially for the kids. This is therapeutic for them, and educational, too.

There are some things I can not tell you about because you’re not prepared for it.

There’s some startling things that are starting to come out today. It takes years to be prepared in the rituals.

Dummbun means “clever Murray” — a black shaman, somebody who can do these things.

So much has been lost and young people are being told things about their own culture that are wrong. One of the things that is said is that Aboriginal people don’t own anything, but that is not right: people did own things, like spears they worked for years on it, or their land where their ancestors lived forever. But they also shared many things.

(I asked Geoff about the book “Mutant Message from Down Under” and he winced.) There is no word for “mutant” in any of the 10 Aboriginal languages I know: there’s not even a concept for it.

Instead, we’re interested in what we call “clever” messages and ways.

I was first initiated as a man when I was 18 years old. I went to a place in the northern territories where they wanted a stockman, and had hired me by the mail because of my reputation and background. I didn’t say anything about my aboriginal heritage to them; this was just after the war, and I’d passed as white in the Army.

But before I got there, the old people looked into the place they look to know all things, and saw that I was Aboriginal. So they told everybody there was a Murray coming to run the camp, but the other Murrays there knew this was a racist station, and so they all said it couldn’t be: those white owners would never hire a Murray as a stockman, a manager. So when I got there the kids ran back and said that I was a white man, because my skin is so light. They said the old people had been wrong in what they’d seen in the signs.

There was a girl sulking there, who told me that I didn’t know the Murray ways, and she mentioned the Guana (my totem, which is like a big lizard). She said that the head clever man, one of the old men, had said that a Guana man was coming, and this shocked me, because I am a Guana man, but I didn’t say anything, I let them think I was white like the owners did.

And so I drafted up the horses, but the stockmen, the Murray ringers, were running the old Murrays down, making fun of them for what they’d said about me before I came. “Ah, they dreamed a Guana man Murray was going to come, how stupid.”

We moved that night and some of the old people followed us along with the young men and the stock animals. The young men expected the stock to run from my ’white’ smell, and then they’d be able to steal my food. But it didn’t happen, because the animals knew who I was.

Then over dinner, one of the young fellows said, “Boss, can you eat guana?” and I said no, and he started to sit up straighter, said, “Are you a Murray?”

“Yes,” I said, so they offered me a meal, which is a sign of brotherhood, of acceptance.

I knew of corruption among the white bookkeepers, and so I got some flour, salt, and syrup and gave it to the men, because the whites had been keeping it for themselves and marking it down as Murray rations. Then I confronted the bookkeeper and got the Murray ration for them that the bookkeeper had been stealing. I forced him to hand out the tucker. And so the Murrays there, they accepted me as family.

And so that was when the old people first began to teach me the ways and secrets of my people, so I eventually became a clever fellow.

The training was season by season. Different things are learned at different times, when a certain fruit or flower is on, everything from each season, at the time of that season. The moon and stars, the weather, the times of year, the plants and animals, they all have their seasons and times, and you must learn the right thing at the right time. It’s why it can’t be in a book: this is an oral tradition, a teaching from one to another. It can only be that way.

Just visited a family/station at Parnable, where they’re having a problem with gold prospectors setting fires.

Thom’s journal:

Earlier, we had passed tadpole rock, where all tadpoles in the world originated. Geoff said that before a man could take a wife, he first had to perform a ceremony on the rock. Now there are no more ceremonies, which may account for why tadpoles are dying all over the world. Geoff had heard the story for years, but once he saw it from a plane and it’s a perfect tadpole.

Parmaill - Geoff says that in the gold mining days, there were four sets of laws. One for the wealthy, one for the poor white miners, one for the Chinese, and one for the Aboriginals, in that order. It was an informal system, but rigidly followed.

When we got out into the bush, after the first night and morning, I was violently ill. Geoff took my pulses and then hurt/massaged me, literally walking on my back and the back of my legs. I slept half the day after that, nearly comatose. I woke up feeling tired and sore, dizzy and weak. My stomach hurt, and my head felt like I had the worse hangover of my whole life.

Two days before I’d flown 27 hours from Burlington, Vermont to Chicago, Los Angeles, Sydney, and then to Cairns in northeast Australia, then, upon arrival, given a 4-hour speech to a group of doctors, therapists, teachers, and parents, then the next morning drove all day out to Petford, to Geoff’s place.

We picked up 4 kids and supplies and, around 2 pm left for the Lockhart River Aboriginal community, a few days travel through the bush to the north. We drove until just before sundown when we arrived at the Mitchell river, after driving for several hours over a rutted trail that Geoff insisted was the main highway although no car could possibly have traveled it. We crossed rivers three feet deep and ten feet wide, with our Land Cruiser’s air intake pipe run up to the roof so the truck could run even when the engine was underwater.

We arrived and made camp, boiled some river water and cooked rice and dried vegetables, and went to sleep under the stars to the sound of insects and tropical birds.

It sounded like a wet twig snapping or breaking that woke me, followed by a splash in the Mitchell river about ten feet from my bedroll. I opened my eyes and could still see a few stars in the early morning sky as Geoff ran by me, barefoot, nearly silent, toward the water. He was chasing a 5-foot freshwater crocodile with a blue crane in its mouth.

When I got up, I took a drink of water with Greens Plus in it, immediately threw up, and began to tremble. I sat down to avoid passing out. Geoff came over and took my pulse, using the same 3-finger method I’d learned in China. He said it was very bad, that my heart was running with long, ropy beats, and that my liver was inflamed. The whites of my eyes were yellow. It’s hepatitis, or you’ve been poisoned, he said. This is very dangerous. In mid-sentence of my reply I laid down and passed out. Four hours later, around 10 am, I woke up, still feeling like it wouldn’t surprise me if I were to die, and it may even be a relief.

Geoff took my pulse again and said he’d been watching me. Asked if he could try some traditional medicine work on me, and I said ok. He laid me on my stomach and gave me the most painful massage, from head to toe, of my life. There were a few spots that normally wouldn’t be at all painful, like the back of my left calf, that hurt just to the touch, and he said that was a liver point and dug into it until I had tears in my eyes. When he was finished, I passed out again. Late afternoon I came back to, feeling totally alive and refreshed. I got out my tape recorder and camera and Zaurus and we talked for hours until dinnertime about his life and ancient Aboriginal ways.

Just crossed the Allabout boundary and Geoff found a hardly-visible rutted trail through the bush which we followed back to a huge rock formation erupting out of the plain. This is a story place, he said. When we’re here we must be careful not to disturb anything -- we leave behind only our tracks. And we must not call each other by name, as then the Quinkens, if there are any around, will know who we are and can follow us and cause problems.

Biting green ants crawled up my leg and, passing through some brush, huge black and white-striped spiders fell on me. It spooked the four boys with us.

The Aboriginal boys with us were upset because in our haste to leave this morning we’d forgotten to smoke ourselves.

I asked Geoff about the books that purport to tell about Aboriginal prophecy, or that the Aboriginal people are going to commit suicide or something else at the end of the millenium. He seemed sad, and said:

Aboriginal prophecy has mostly to do with what will happen if or when laws are broken. “Ah, yeah, they’re broken badly now, all these white fellas killing the animals, dirtying the rivers, changing their course, drilling from the earth.” What will happen? “The Great Spirit will wreck everything, start over.”

The real secrets about how the universe works and what the future may hold are not hidden, they’re obvious for everybody to see.

It’s the ways of life for each tribe that make that tribe unique that are secret, are hidden, because each is what defines the identity of its own people. But they are not the laws of the universe or the ultimate truths - those are obvious. They’re only the ways of this people or that.

And to reveal them in a book or by some tourist show or something like that is very disrespectful.

When somebody says or writes that they’ve been told this secret or that by a tribal people, what they are saying is that somebody in some tribe trusted and respected them enough to share with them the details of their identity, who they are and what makes them who they are. Sort of like if your neighbor told you the intimate details of his relationship with his wife or his father. If that person then blabs those details around, it’s not a “revealing of the truth” or any such thing — it’s merely bad manners and a demonstration of a boorish lack of respect, discretion, and the ability to honor a friendship and confidence. Or it is a collection of lies for the purpose of self-aggrandizement or to make money, a profaning of the intimate and human.

When I was about 8, on the station, there was this bloke who was a madman. Everybody was afraid of him. If you crossed him, he’d come after you with the blunt side of an axe, and he beat many men bloody. He was also a fighter, he’d been the heavyweight champion of the Australian Navy. But I got along with him ok, and a bit before I got the big flogging and stopped talking, he took me aside one day and asked me, do you want to learn how to read? And I said sure, and so he took out the only book he owned, which was his dead mother’s Bible, and that’s the book I learned to read from.

Animals tell you of things that are happening, but they don’t predict the future like some say — there are too many variables. I knew one fellow who was a crocodile person and was always trying to get in with his people and ended up with a big scar down his leg. Always trying to climb up on top of a crock, to be with his people.

Many people believe they can predict the future by signs. A dumben (doctor) clever Murray fellow can do that. But most predictions are if somebody destroys something or breaks some rule. Generally, we don’t do divination. If you go to a sacred place where the Rainbow Serpent is supposed to be, that can cause a flood or some other problem. There is an island off of Normantown, and the Island people used to pay other Murrays a tribute not to swim through a hole in the reef because their tradition said that when people swam through that hole, then cyclones would come.

We have known forever about places where there is a lot of gold, for example, but you can’t mine it because we’ve been told you can’t take from that land. It belongs to the land.

The wind can give your secrets away, can tell that tree that might be a friend of that wallaby and give your secrets away. So you be careful not to talk when there’s a wind. Because that tree is a thing and that wallaby is a thing and they’re all alive and conscious and must be respected and they all have life and want life, and they’re listening.

One thing we need to remember, because I’ve been on so many Murray communities, is that my thoughts could be contaminated and my thoughts may be mine and not those of all Aboriginals. It was different in the old days; people didn’t move around and the stories were more true and more powerful. Like the story about the black mountain and the flying foxes in that place we visited that you can’t write about.

Some places of the Rainbow Serpent you can’t even say his name, and these young people who haven’t been initiated can’t even say his name at all. He has a special name which has great power — Rainbow Serpent is just how he is described, it’s not his Name. When initiated men do talk about him, it’s very respectful and they do it with pride, you know?

Family groups were connected by marriage into clans, but there were no “tribes.” At certain times of the year when a lot of mullet might be running, they’d come together for a corrobary (like a potlatch or powwow) which is also a contaminated word but is used across Australia now. Corrobary is a “shake a leg” or a dance. I think the word came from southern Queensland. But you can go to any Aboriginal group now and say you’re going to have a corroboray and they know what you mean.

Magic

There was this fellow named Arthur Bundai back in the days just as the prickly pear was getting cleaned up, so that was in the 1930s, and his brother had gone down to Taroom spearing and poisoning the pears. But the pear was starting to die up from the beetle, and so he got a job as a stockman. He got mixed up with some girl there and some caught him with this girl and killed him with magic (don’t know just how) called “puri puri.”

And so a relative took some of his hair back to the old people, and they twisted it together with some of his blood and got all the families associated with him around the fire and saw which way the hair fell over, and it fell toward one of the families, meaning that was the family that killed him. And it was Arthur’s job to go pay back that family. (It was his brother who got killed).

And he’d been brought up as a stockman and knew about the Old People’s way but he didn’t know the details of the Old People’s ways, he wasn’t a clever fellow, he knew no magic. So he stole the head stockman’s Webly revolver with the intention of killing the whole family who killed his brother. And that was a long ride, a fortnight’s horse ride, and he rode down there, found a good place to camp his horse to feed, and watched the camp for a couple of days, and one night he plucked up courage to go and do the job.

Those fellows had a tin shack — just one room with a doorway — but those fellows, at nighttime, they’d put a chain on that door, and he goed down there late in the night when the fire went low and he knocked on the door, yeah, and said, “Hey, you fellas, I got grog here.” And they’re a bit frightened by the strange voice and said, “Hey, who you?”

And he called out “I got flagon.” But them fellers were still a bit frightened and said “we don’t know you, so go away.” But he knew they’re not going to open that door, so he’ s trying to open the chain and it’s making some noise so he’s getting really frightened. And then all at once something grabbed his neck and made a huge noise like a Kangaroo, Kgghhhhhh (when they kick adds Michael).

And they’s this fella standing there hanging on his neck, called the Gray Ghost. By this time Arthur is frightened, but this fellow makes a sign that he’s gonna kill them all in the house, point’n and making signs. So that was enough for Arthur, so he clear out to his camp and got on his horse and ran away. But eventually all that family, over several months, all died in their sleep, caught one by one, even when they took the kid away to another camp they found themselves chained up or hung, and they were all dead.

The Gray Ghost

Long time back the only way a Murray could get work was ring-barking, and there was this family and the only way they could get money was from ring-barking trees so they’d die and fall over. And all the money had to go to the bank at the station. And then you had to get your money back from the police station. And this husband and wife were doing ring-barking on a 30,000 acre paddy and they’d do a strip a few kilometers long and 200 feet wide, keep shifting camp so the camp was always by where they were working.

And this woman was ring-barking too and she had a little baby in a cradle, a kooliman, carved out of a bottle tree or one of the soft trees, and had the baby in this. And the husband told her to go back, because there might be crow or dingo or gurana that could worry (bewitch) the baby. And she went off and continued ring-barking anyway just a distance away. And then he heard her scream and when they caught up with her, found her, they discovered that somebody had swapped the baby.

And it was a proper baby but it was gray color, but a boy the same age. And this fellow the husband got wild, thought it was some magic, and so he blamed his woman and hit her with an axe and broke her jaw. And he went looking for the tracks of who may have switched the babies, but couldn’t find any. And when that woman came to, she took the baby and ran off into the bush to raise him. And as that baby grew up, he couldn’t talk, just make this funny noise, and when he got bigger, he used to live on the edge of town and nobody would go near her much, you know.

It wouldn’t matter how hot or cold it was, he used to wear a WWI army trench coat (after the war, the soldiers returning would leave their gear around or throw it away and the Murrays would get it somehow or steal it), and possibly Arthur Bondai’s brother had befriended the Gray Ghost, this switched baby, somehow and so the Ghost felt that he had to pay back Bondai for some reason. In later years after the Ghost died, people claimed family to him (he was a real person) but when he was alive even his own family would chase him away.

25 August 1998

We’re at the police station in Lockhart sitting on the grass outside the building with a dozen or so Murrays waiting for the magistrate who flew in this morning to decide to open the doors into the air-conditioned building and start the 9 a.m. court session. As I’m typing these words it’s 10:23 a.m. The police and the magistrate — like all the teachers in the school — are white. The town is Aboriginal.

An old man, gray beard and hair, walks up to join us on the lawn in the hot sun waiting for the police building to open, and Geoff introduces me to him as Gabriel, and he looks at the ground as we’re introduced. Eye contact is bad manners, so I look at the ground, too, and he exhales and drops his shoulders like he’s relaxed now with me.

Earlier we’d driven to the seashore at the edge of town and the boys went swimming and Geoff found a ripe coconut and we had some coconut milk and coconut meat for breakfast.

On the way down, we passed the pickup point for the fellas working on the dole. They were packed onto the back of a flat-bed truck, and a white guy was walking around, getting ready to drive them out to do some road work or trash pickup or whatever other make-work the Council could come up with to justify the dole weekly salary the men all get.

Geoff is sitting on the grass talking with a boy of about 12 who’s here for court. Nicky is his name, and he’s dark brown with a wide mouth and nose, and thick wavy black hair. Nicky was at Petford once before, and now is back again at court for stealing, and Geoff is here hoping he can convince the magistrate to remand Nicky to Petford instead of to the new million-dollar, 60-person jail they’ve recently built next to the police station.

“Hey, mate, you were going to bring me a crayfish meal,” Geoff says to Nicky, who smiles broadly.

“You can get your own,” Nicky says, “There’s the ocean,” pointing to the north.

“But this is your country, mate,” Geoff says. “You know I can’t hunt on your country.”

Nicky nods knowingly. “I’ll get you some, grandfather,” he says to Geoff respectfully. “If they don’t put me in jail.”

Listening to the conversation, I’m suddenly struck by one of the keys to Geoff’s success in working with these kids, who are usually the “most incorrigible” the system has: he understands their culture, respects it, and lives by it. He’s an initiated Clever Fella himself, even though very, very few people know it (including the kids and other Aboriginal people he works with).

He understands the importance of cooperation instead of competition, that people in this culture will be hurt more by shame than by punishment, that they’ll be more motivated by sharing and the good of the group than by individual gain or personal power. In fact, to have personal power in this society is to carry a terrible burden, because if there’s even a hint that it’s used for self-aggrandizement or personal benefit, what follows is both great personal humiliation and social ostracism.

Leadership in this culture is seen as the role of mediation and consensus-building, not having power or lording over others. The way the white senators make laws and decisions for their people without first getting a consensus from the people on each issue is as incomprehensible to the Australian Aborigines as it was to the American Iroquois. That lifelong politicians — “leaders” — like Richard Nixon or Lyndon Johnson or Ferdinand Marcos would come into office poor or middle-class and retire from top leadership posts as multi-millionaires is seen by these people as a sign of great moral failure, a humiliation of both the man who claimed leadership and of his people.

Similarly, Geoff owns just about nothing — in fact, keeping Petford and Strathburn alive has throw him deeply in debt. Anything he has, he shares with his kids or staff.

It’s difficult for me, even having raised my own children and having run a community for these types of (mostly white) kids in the US, to restrain myself from wanting to jump into some of Geoff’s interactions with the kids and assert “adult authority.” I keep reminding myself that what I’m really thinking of asserting is not adult authority but the authority of our dominator, younger culture: hierarchy, decisions made for one person by another, control of one by another.

However, children are not raised this way in Aboriginal society, which has historically caused some white observers to suggest that Aborigines are too permissive in their child-rearing. But at puberty, in their culture as it was lived out for 50,000 years, childhood is set aside and the kids take on their roles of adulthood with a self-confidence and knowledge of self and family and place that they’ve in reality been preparing for all their lives.

Geoff: The true name of the Creator is unspeakable except by those initiated, and only then on very holy occasions. And, of course, different tribes have different names and ways and stories about the Creator: the story of the Rainbow Serpent is one of the most common.

But I know of no story of a fall from grace, of a story that says that man was once good and then became evil, or, particularly, that such a tragic event happened and that it was the fault of a woman. This is a very weird idea.

Women are held in high esteem, and humans are holy, as is all creation. Can you imagine a god who would hate us so much as to punish you and me for the mistake of a single woman thousands of years ago? This seems crazy to most Aboriginal people.

There are three categories of knowledge: things that can be told and written, things that can be told but not written, and things that cannot be told outside the group. You may, of course, only write the first category.

But the real stories, the true power stories, the meaning of life and how to live, these are not secrets. They are obvious to all people, and anybody who thinks about it for even a little bit can figure them out.

It’s the private ways of an individual tribe or people, of little groups like mine, that are secret. Not because they’re the greatest secrets, but just because it’s correct behavior to respect other people’s privacy.

Geoff: Not everybody can pray, and you can’t do it just any time. You have to first purify yourself and also be an initiate. Prayer is never for things, never requests. It’s always to get strength and guidance.

There are specific places where you can pray. Not just story places, but origin places. Where the Rainbow Serpent came up from the earth, or where he stayed, or where his cave is, like that.

To ask for things, there are special ceremonies. They vary from group to group. One group believes if they swim through a coral reef that brings the cyclones. Another group used to pay them tribute so they wouldn’t do it. Some people believe if you break laws you can cause drought, winds, etc.

The Fire Story of Geoff’s people:

Some of my mob in the south didn’t have fire and there was one fellow named Burray born with a club foot and they were going to hit him on the head when he was a baby but they decided he was strong and to let him live. Bit older, kill him but he’s strong, let him live. Then he got hairy around the groin and they had to finish him, so instead they banished him from his home country and he headed north.

He goes a long way, walk, walk, and he’s got to dodge people because he’s a stranger, you know. And then he come to one mob that’s dancing and they got fire, and he’s never seen fire. And one time they left a wallaby in a ground oven, and he sneaked and stole some and ate it and reckoned this is good. And he saw how they used the fire to make spear points hard. And for six months he watched them and learned how they made fire, fire sticks, how to keep the fire.

And one day he makes up his mind he’s going to steal a fire-stick, and around 3am and everybody is asleep he goes for the stick and one little baby woke up and tried to wake its parents, but the parents said go back to sleep.

In the morning the parents and tribe found the tracks of this club foot fellow, and were worried that maybe he was there to make magic, and they tracked him, but he hid his stool so they couldn’t make magic of it. Different tribes sent smoke so the tribes would follow him, but he avoided them.