Yesterday was the anniversary of the Boston Tea Party: it happened exactly 250 years ago. And once again there’s a growing movement in America to push back against monopolistic corporate power. So, here’s an edited excerpt from my book Unequal Protection: How Corporations Became “People”…

Conventional wisdom has it that the 1773 Tea Act — a tax law passed in London that led to the Boston Tea Party — was simply an increase in the taxes on tea paid by American colonists. In reality, however, the Tea Act gave the world’s largest transnational corporation — The East India Company — full and unlimited access to the American tea trade, and exempted the Company from having to pay taxes to Britain on tea exported to the American colonies. It even gave the Company a tax refund on millions of pounds of tea they were unable to sell and holding in inventory.

The primary purpose of the Tea Act was to increase the profitability of the East India Company to its stockholders (which included the King and the wealthy elite that kept him secure in power), and to help the Company drive its colonial small-business competitors out of business. Because the Company no longer had to pay high taxes to England and held a monopoly on the tea it sold in the American colonies, it was able to lower its tea prices to undercut the prices of the local importers and the mom-and-pop tea merchants and tea houses in every town in America.

This infuriated the independence-minded American colonists, who were wholly unappreciative of their colonies being used as a profit center for the world’s largest multinational corporation, The East India Company. They resented their small businesses still having to pay the higher, pre-Tea Act taxes without having any say or vote in the matter. (Thus, the cry of “no taxation without representation!”) Even in the official British version of the history, the 1773 Tea Act was a “legislative maneuver by the British ministry of Lord North to make English tea marketable in America” with a goal of helping the East India Company quickly “sell 17 million pounds of tea stored in England…”

America’s first entrepreneurs’ protest

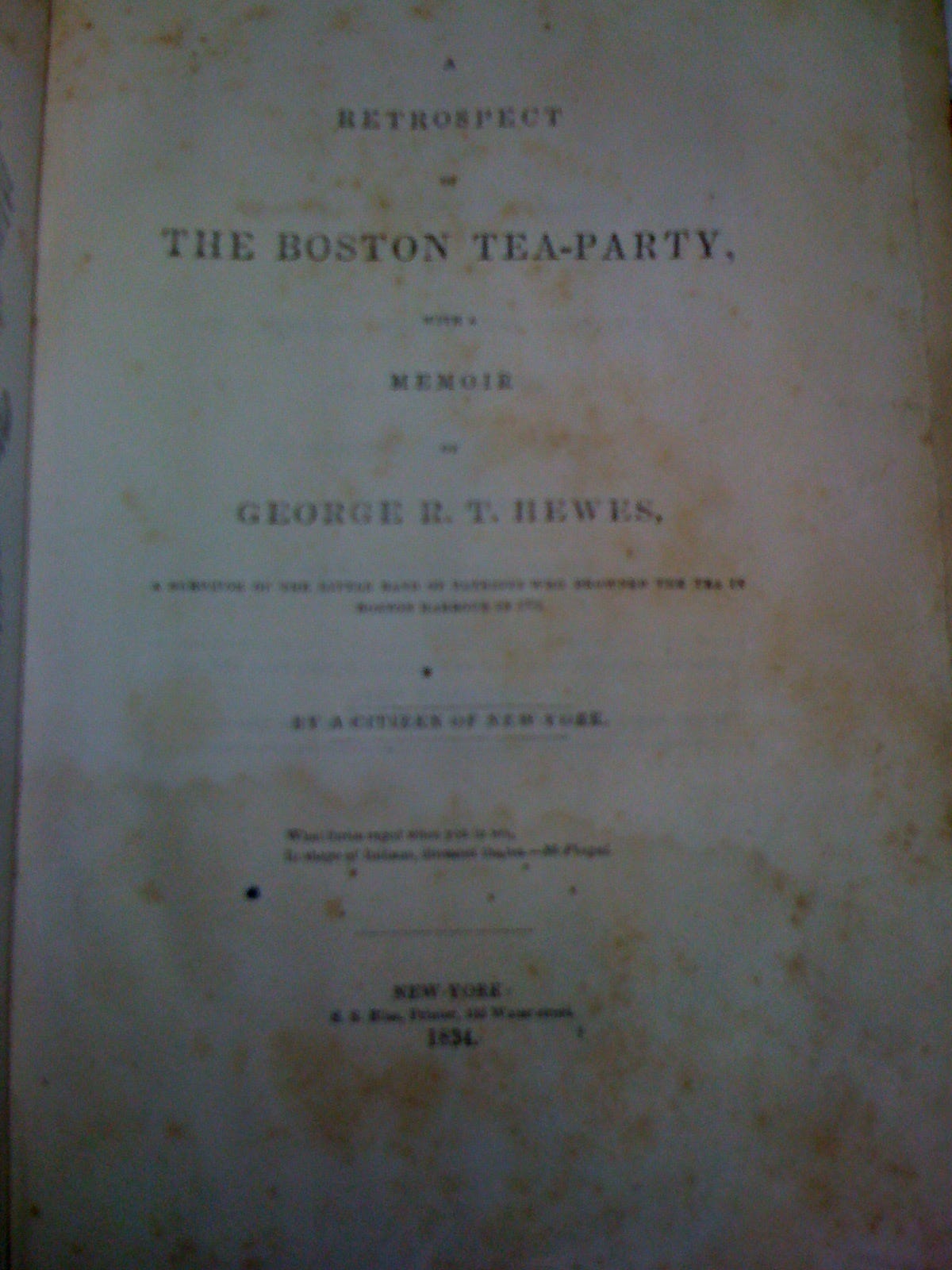

This economics-driven view of American History piqued my curiosity when I first discovered it. So when I came upon an original first edition of one of this nation’s earliest history books, I made a sizeable investment to buy it to read the thoughts of somebody who had actually been alive and participated in the Boston Tea Party and subsequent American Revolution. I purchased from an antiquarian book seller an original copy of Retrospect of the Boston Tea Party with a Memoir of George R.T. Hewes, a Survivor of the Little Band of Patriots Who Drowned the Tea in Boston Harbor in 1773, published in New York by S. S. Bliss in 1834.

Because the identities of the Boston Tea Party participants were hidden (other than Samuel Adams) and all were sworn to secrecy for the next fifty years, this account (published 61 years later) is singularly rare and important, as it’s the only actual first-person account of the event by a participant that exists, so far as I can find. And turning its brittle, age-colored pages and looking at printing on unevenly-sized sheets, typeset by hand and printed on a small hand press almost two hundred years ago, was both fascinating and exciting. Even more interesting was the perspective of the anonymous (“by a citizen of New York”) author and of Hewes, whom the author extensively interviewed for the book.

Although Hewes’ name is today largely lost in history, he was apparently well known in colonial times and during the 19th century. Esther Forbes’ classic 1942 biography of Paul Revere, which depended heavily on Paul Revere’s “many volumes of papers” and numerous late 18th and early 19th century sources, mentions Hewes repeatedly throughout her book. For example, when young Paul Revere went off to join the British army in the spring of 1756, he took along with him Hewes.

“Paul Revere served in Richard Gridley’s regiment,” Forbes writes, noting Revere’s recollection that the army had certain requirements for its recruits. “All must be able-bodied and between seventeen and forty-five, and must measure to a certain height. George Robert Twelvetrees Hewes could not go. He was too short, and in vain did he get a shoemaker to build up the inside of his shoes; but Paul Revere ‘passed muster’ and ‘mounted the cockade.’”

And when it came to the Boston Tea Party, Forbes notes, “No one invited George Robert Twelvetrees Hewes, but no one could have kept him home.” She quotes him as to the size of the raiding party, noting “Hewes says there were one hundred to a hundred and fifty ‘indians’” that night.

Hewes apparently came to Boston through the good graces of America’s first president.

“George Robert Twelvetrees Hewes fished nine weeks for the British fleet until he saw his chance [to escape] and took it,” writes Forbes. “Landing in Lynn, he was immediately taken to [George] Washington at Cambridge. The General enjoyed the story of his escape — ‘he didn’t laugh to be sure but looked amazing good natured, you may depend.’ He asked him to dine with him, and Hewes says that ‘Madam Washington waited upon them at table at dinner-time and was remarkably social.’ Hewes was one of the many Boston refugees who never went back there to live. Having served as a privateersman and soldier during the war, he settled outside of the state.”

And there, outside the state, was where Hewes lived into his old age, finally telling his story to those who would listen, including one who published the little book I found.

That frightful night

Reading Hewes’ account, I learned that the Boston Tea Party resembled in many ways the growing modern-day protests against transnational corporations and small-town efforts to protect themselves from chain-store retailers or factory farms. With few exceptions, the Tea Party’s participants thought of themselves as protesters against the actions of the multinational East India Company and the government that “unfairly” represented, supported, and served the company while not representing or serving them, the residents.

Hewes noted that many American colonists either boycotted the purchase of tea, or were smuggling or purchasing smuggled tea to avoid supporting the East India Company’s profits and the British taxes on tea, which, according to Hewes’ account of 1773, “rendered the smuggling of [tea] an object and was frequently practiced, and their resolutions against using it, although observed by many with little fidelity, had greatly diminished the importation into the colonies of this commodity. Meanwhile,” Hewes noted, “an immense quantity of it was accumulated in the warehouses of the East India Company in England. This company petitioned the king to suppress the duty of three pence per pound upon its introduction into America…”

That petition was successful and produced the Tea Act of 1773: the result was a boom for the transnational East India Company corporation, and a big problem for the entrepreneurial American “smugglers.”

As Hewes notes:

“The [East India] Company, however, received permission to transport tea, free of all duty, from Great Britain to America…” allowing it to wipe out its small competitors and take over the tea business in all of America. “Hence,” he told his biographer, “it was no longer the small vessels of private merchants, who went to vend tea for their own account in the ports of the colonies, but, on the contrary, ships of an enormous burthen, that transported immense quantities of this commodity, which by the aid of the public authority, might, as they supposed, easily be landed, and amassed in suitable magazines. Accordingly the Company sent its agents at Boston, New York, and Philadelphia, six hundred chests of tea, and a proportionate number to Charleston, and other maritime cities of the American continent. The colonies were now arrived at the decisive moment when they must cast the dye, and determine their course…”

Interestingly, Hewes notes that it wasn’t just American small businesses and citizens who objected to the new monopoly powers granted the East India Company by the English Parliament. The East India Company was also putting out of business many smaller tea exporters in England, who had been doing business with American family-owned retail stores for decades, and those companies began a protest in England that was simultaneous with the American protests against transnational corporate bullying and the East India Company’s buying of influence with the British Parliament.

Hewes notes:

“Even in England individuals were not wanting, who fanned this fire; some from a desire to baffle the government, others from motives of private interest, says the historian of the event, and jealousy at the opportunity offered the East India Company, to make immense profits to their prejudice.

“These opposers [sic] of the measure in England [the Tea Act of 1773] wrote therefore to America, encouraging a strenuous resistance. They represented to the colonists that this would prove their last trial, and that if they should triumph now, their liberty was secured forever; but if they should yield, they must bow their necks to the yoke of slavery. The materials were so prepared and disposed that they could easily kindle.”

The battle between the small businessmen of America and the huge multinational East India Company actually began in Pennsylvania, according to Hewes.

“At Philadelphia,” he writes, “those to whom the teas of the [East India] Company were intended to be consigned, were induced by persuasion, or constrained by menaces, to promise, on no terms, to accept the proffered consignment.

“At New-York, Captains Sears and McDougal, daring and enterprising men, effected a concert of will [against the East India Company], between the smugglers, the merchants, and the sons of liberty [who had all joined forces and in most cases were the same people]. Pamphlets suited to the conjecture, were daily distributed, and nothing was left unattempted by popular leaders, to obtain their purpose.”

Resistance was organizing and growing and the Tea Act was the final straw. The citizens of the colonies were preparing to throw off one of the corporations that for almost two hundred years had determined nearly every aspect of their lives through its economic and political power. They were planning to destroy the goods of the world’s largest multinational corporation, intimidate its employees, and face down the guns of the government that supported it.

A pamphlet was circulated through the colonies called The Alarm and signed by an enigmatic “Rusticus.” One issue made clear the feelings of colonial Americans about England’s largest transnational corporation and its behavior around the world:

“Are we in like Manner to be given up to the Disposal of the East India Company, who have now the Assurance, to step forth in Aid of the Minister, to execute his Plan, of enslaving America? Their Conduct in Asia, for some Years past, has given simple Proof, how little they regard the Laws of Nations, the Rights, Liberties, or Lives of Men. … Fifteen hundred Thousands, it is said, perished by Famine in one Year, not because the Earth denied its Fruits; but [because] this Company and their Servants engulfed all the Necessaries of Life, and set them at so high a Rate that the poor could not purchase them.”

The pamphleteering worked

After turning back the Company’s ships in Philadelphia and New York, Hewes writes, “In Boston the general voice declared the time was come to face the storm.”

He writes about the sentiment among the colonists who opposed the naked power and wealth of the East India Company and the British government that supported them:

“Why do we wait? they exclaimed; soon or late we must engage in conflict with England. Hundreds of years may roll away before the ministers can have perpetrated as many violations of our rights, as they have committed within a few years. The opposition is formed; it is general; it remains for us to seize the occasion. The more we delay the more strength is acquired by the ministers. Now is the time to prove our courage, or be disgraced with our brethren of the other colonies, who have their eyes fixed upon us, and will be prompt in their succor if we show ourselves faithful and firm.

“This was the voice of the Bostonians in 1773. The factors who were to be the consignees of the tea, were urged to renounce their agency, but they refused and took refuge in the fortress. A guard was placed on Griffin’s wharf, near where the tea ships were moored. It was agreed that a strict watch should be kept; that if any insult should be offered, the bell should be immediately rung; and some persons always ready to bear intelligence of what might happen, to the neighbouring towns, and to call in the assistance of the country people.”

“Rusticus” added his voice, the May 27, 1773 pamphlet saying:

“Resolve therefore, nobly resolve, and publish to the World your Resolutions, that no Man will receive the Tea, no Man will let his Stores, or suffer the Vessel that brings it to moor at his Wharf, and that if any Person assists at unloading, landing, or storing it, he shall ever after be deemed an Enemy to his Country, and never be employed by his Fellow Citizens.”

Colonial voices were getting louder and louder about their outrage at the giant corporation’s behavior. A pamphlet titled The Alarm wrote on October 27, 1773:

“It hath now been proved to you, That the East India Company, obtained the monopoly of that trade by bribery, and corruption. That the power thus obtained they have prostituted to extortion, and other the most cruel and horrible purposes, the Sun ever beheld.”

The corporation challenges the people

And then, Hewes says, on a cold November evening, the first of the East India Company’s ships of tax-free tea arrived.

“On the 28th of November, 1773,” Hewes writes, “the ship Dartmouth with 112 chests arrived; and the next morning after, the following notice was widely circulated.

“Friends, Brethren, Countrymen! That worst of plagues, the detested TEA, has arrived in this harbour. The hour of destruction, a manly opposition to the machinations of tyranny, stares you in the face. Every friend to his country, to himself, and to posterity, is now called upon to meet in Faneuil Hall, at nine o’clock, this day, at which time the bells will ring, to make a united and successful resistance to this last, worst, and most destructive measure of administration.”

The reaction to the pamphlet — back then one part of what was truly a “free press” in America — was emphatic. Hewes account was that:

“Things thus appeared to be hastening to a disastrous issue. The people of the country arrived in great numbers, the inhabitants of the town assembled. This assembly which was on the 16th of December, 1773, was the most numerous ever known, there being more than 2000 from the country present.”

Hewes continued:

“This notification brought together a vast concourse of the people of Boston and the neighbouring towns, at the time and place appointed. Then it was resolved that the tea should be returned to the place from whence it came in all events, and no duty paid thereon. The arrival of other cargoes of tea soon after, increased the agitation of the public mind, already wrought up to a degree of desperation, and ready to break out into acts of violence, on every trivial occasion of offence....

“Finding no measures were likely to be taken, either by the governor, or the commanders, or owners of the ships, to return their cargoes or prevent the landing of them, at 5 o’clock a vote was called for the dissolution of the meeting and obtained. But some of the more moderate and judicious members, fearing what might be the consequences, asked for a reconsideration of the vote, offering no other reason, than that they ought to do every thing in their power to send the tea back, according to their previous resolves. This, says the historian of that event[1], touched the pride of the assembly, and they agreed to remain together one hour.”

The people assembled in Boston at that moment faced the same issue that citizens who oppose combined corporate and co-opted government power all over the world confront today: should they take on a well-financed and heavily armed opponent, when such resistance could lead to their own imprisonment or death? Even worse, what if they should lose the struggle, leading to the imposition on them and their children an even more repressive regime to support the profits of the corporation?

There are corporate spies among us!

There was a debate late that afternoon in Boston, Hewes notes, but it was short because a man named Josiah Quiney pointed out that some of the people in the group worked directly or indirectly for the East India Company, or held loyalty to Britain, or both. Quiney suggested that if they took the first step of confronting the East India Company, it would inevitably mean they would have to take on the army of England. He pointed out they were really discussing the possibility of going to war against England to stop England from enforcing the East India Company’s right to run its “ministerial enterprise,” and that some who profited from that enterprise were right there in the room with them.

In Hewes’ book, he wrote:

“In this conjuncture, Josiah Quiney, a man of great influence in the colony, of a vigorous and cultivated genius, and strenuously opposed to ministerial enterprises, wishing to apprise his fellow-citizens of the importance of the crisis, and direct their attention to probable results which might follow, after demanding silence said, ‘This ardour and this impetuosity, which are manifested within these walls, are not those that are requisite to conduct us to the object we have in view; these may cool, may abate, may vanish like a flittering shade. Quite other spirits, quite other efforts are essential to our salvation. Greatly will he deceive himself, who shall think, that with cries, with exclamations, with popular resolutions, we can hope to triumph in the conflict, and vanquish our inveterate foes. Their malignity is implacable, their thirst for vengeance insatiable. They have their allies, their accomplices, even in the midst of us - even in the bosom of this innocent country; and who is ignorant of the power of those who have conspired our ruin? Who knows not their artifices? Imagine not therefore, that you can bring this controversy to a happy conclusion without the most strenuous, the most arduous, the most terrible conflict; consider attentively the difficulty of the enterprise, and the uncertainty of the issue. Reflict [sic] and ponder, even ponder well, before you embrace the measures, which are to involve this country in the most perilous enterprise the world has witnessed.’”

Most Americans today believe that the colonists were only upset that they didn’t have a legislature they’d elected that would pass the laws under which they were taxed: “taxation without representation” was their rallying cry. And while that was true, Hewes points out, the needle in their side, the pinprick that was really driving their rage, was that England was passing tax laws solely for the benefit of the transnational East India Company corporation, and at the expense of the average American worker and America’s small business owners.

Thus, “Taxation without representation” also meant hitting the average person and small business with taxes, while letting the richest and most powerful corporation in the world off the hook for its taxes. It was government sponsorship of one corporation over all competitors, plain and simple.

And the more the colonists resisted the predations of the East India Company and its British protectors, the more reactive and repressive the British government became, arresting American entrepreneurs as smugglers and defending the trade interests of the East India Company.

Among the reasons cited in the 1776 Declaration of Independence for separating America from Britain are: “For cutting off our Trade with all parts of the world: For imposing Taxes on us without our Consent.” The British had used tax and anti-smuggling laws to make it nearly impossible for American small businesses to compete against the huge multinational East India Company, and the Tea Act of 1773 was the final straw.

Thus, the group assembled in Boston responded to Josiah Quiney’s comment by calling for a vote. The next paragraph in Hewes’ book says: “The question was then immediately put whether the landing of the tea should be opposed and carried in the affirmative unanimously. Rotch [a local tea seller], to whom the cargo of tea had been consigned, was then requested to demand of the governor to permit to pass the castle [return the ships to England]. The latter answered haughtily, that for the honor of the laws, and from duty towards the king, he could not grant the permit, until the vessel was regularly cleared. A violent commotion immediately ensued; and it is related by one historian of that scene, that a person disguised after the manner of the Indians, who was in the gallery, shouted at this juncture, the cry of war; and that the meeting dissolved in the twinkling of an eye, and the multitude rushed in a mass to Griffin’s wharf.”

A first person account of the Tea Party

On what happened next, Hewes is quite specific in pointing out that not only were the protesters registering their anger and upset over domination by England and the Company, but they were willing to commit a million-dollar act of vandalism to make their point. Hewes says:

“It was now evening, and I immediately dressed myself in the costume of an Indian, equipped with a small hatchet, which I and my associates denominated the tomahawk, with which, and a club, after having painted my face and hands with coal dust in the shop of a blacksmith, I repaired to Griffin’s wharf, where the ships lay that contained the tea. When I first appeared in the street after being thus disguised, I fell in with many who were dressed, equipped and painted as I was, and who fell in with me and marched in order to the place of our destination.

“When we arrived at the wharf, there were three of our number who assumed an authority to direct our operations, to which we readily submitted. They divided us into three parties, for the purpose of boarding the three ships which contained the tea at the same time. The name of him who commanded the division to which I was assigned was Leonard Pitt. The names of the other commanders I never knew.

“We were immediately ordered by the respective commanders to board all the ships at the same time, which we promptly obeyed. The commander of the division to which I belonged, as soon as we were on board the ship appointed me boatswain, and ordered me to go to the captain and demand of him the keys to the hatches and a dozen candles. I made the demand accordingly, and the captain promptly replied, and delivered the articles; but requested me at the same time to do no damage to the ship or rigging.

“We then were ordered by our commander to open the hatches and take out all the chests of tea and throw them overboard, and we immediately proceeded to execute his orders, first cutting and splitting the chests with our tomahawks, so as thoroughly to expose them to the effects of the water.

“In about three hours from the time we went on board, we had thus broken and thrown overboard every tea chest to be found in the ship, while those in the other ships were disposing of the tea in the same way, at the same time. We were surrounded by British armed ships, but no attempt was made to resist us.

“We then quietly retired to our several places of residence, without having any conversation with each other, or taking any measures to discover who were our associates; nor do I recollect of our having had the knowledge of the name of a single individual concerned in that affair, except that of Leonard Pitt, the commander of my division, whom I have mentioned. There appeared to be an understanding that each individual should volunteer his services, keep his own secret, and risk the consequence for himself. No disorder took place during that transaction, and it was observed at that time that the stillest night ensued that Boston had enjoyed for many months.”

The participants were absolutely committed that none of the East India Company’s tea would ever again be consumed on American shores. Hewes continues: “During the time we were throwing the tea overboard, there were several attempts made by some of the citizens of Boston and its vicinity to carry off small quantities of it for their family use. To effect that object, they would watch their opportunity to snatch up a handful from the deck, where it became plentifully scattered, and put it into their pockets.

“One Captain O’Connor, whom I well knew, came on board for that purpose, and when he supposed he was not noticed, filled his pockets, and also the lining of his coat. But I had detected him and gave information to the captain of what he was doing. We were ordered to take him into custody, and just as he was stepping from the vessel, I seized him by the skirt of his coat, and in attempting to pull him back, I tore it off; but, springing forward, by a rapid effort he made his escape. He had, however, to run a gauntlet through the crowd upon the wharf nine each one, as he passed, giving him a kick or a stroke.

“Another attempt was made to save a little tea from the ruins of the cargo by a tall, aged man who wore a large cocked hat and white wig, which was fashionable at that time. He had slightly slipped a little into his pocket, but being detected, they seized him and, taking his hat and wig from his head, threw them, together with the tea, of which they had emptied his pockets, into the water. In consideration of his advanced age, he was permitted to escape, with now and then a slight kick.

“The next morning, after we had cleared the ships of the tea, it was discovered that very considerable quantities of it were floating upon the surface of the water; and to prevent the possibility of any of its being saved for use, a number of small boats were manned by sailors and citizens, who rowed them into those parts of the harbor wherever the tea was visible, and by beating it with oars and paddles so thoroughly drenched it as to render its entire destruction inevitable.”

In all, the 342 chests of tea — over 90,000 pounds — thrown overboard that night were enough to make 24 million cups of tea and were valued by the East India Company at 9,659 Pounds Sterling or, in today’s currency, just over a million U.S. dollars.

In response to the Boston Tea Party, the British Parliament immediately passed the Boston Port Act stating that the port of Boston would be closed until the citizens of Boston reimbursed the East India Company for the tea they’d destroyed. The colonists refused. A year-and-a-half later, the colonists, still refusing to reimburse the corporation, again openly stated their defiance of the East India Company and Great Britain by taking on British troops in an armed conflict at Lexington and Concord (the shots heard ’round the world) on April 19, 1775.

That war — finally triggered by a transnational corporation and its government patrons trying to deny American colonists a fair and competitive local marketplace — would last until 1783.

Jefferson considers “freedom against monopolies” a basic right

Once the Revolutionary War was over, and the Constitution had been worked out and presented to the states for ratification, Jefferson turned his attention to what he and Madison felt was a terrible inadequacy in the new Constitution: it didn’t explicitly stipulate the “natural rights” of the new nation’s citizens, and didn’t protect against the rise of new commercial monopolies like the East India Company.

On December 20th, 1787, Jefferson wrote to James Madison about his concerns regarding the Constitution. He said, bluntly, that it was deficient in several areas:

“I will now tell you what I do not like,” he wrote. “First, the omission of a bill of rights, providing clearly, and without the aid of sophism, for freedom of religion, freedom of the press, protection against standing armies, restriction of monopolies, the eternal and unremitting force of the habeas corpus laws, and trials by jury in all matters of fact triable by the laws of the land, and not by the laws of nations.”

Such a bill protecting natural persons from out-of-control governments or commercial monopolies shouldn’t just be limited to America, Jefferson believed. “Let me add,” he summarized, “that a bill of rights is what the people are entitled to against every government on earth, general or particular; and what no just government should refuse, or rest on inference.”

In 1788 Jefferson wrote about his concerns to several people. In a letter to Mr. A. Donald, on February 7th, he defined the items that should be in a bill of rights:

“By a declaration of rights, I mean one which shall stipulate freedom of religion, freedom of the press, freedom of commerce against monopolies, trial by juries in all cases, no suspensions of the habeas corpus, no standing armies. These are fetters against doing evil, which no honest government should decline.”

Jefferson kept pushing for a law, written into the constitution as an amendment, which would prevent companies from growing so large they could dominate entire industries or have the power to influence the people’s government.

But Federalists including John Adams and Alexander Hamilton fought Jefferson and Madison, and when Congress finally passed the Bill of Rights it no longer contained a ban on corporations owning other corporations or monopolizing industries. In response to that, hundreds of states passed laws restricting and restraining corporations, which were the law of the land until the court reporter of the U.S. Supreme Court incorrectly placed in the headnotes of the Santa Clara County v. Southern Pacific Railroad case of 1886 that “corporations are persons” and entitled to the same rights as humans under the Bill of Rights. In a dangerous (to democracy) and growing trend, corporations have since used that error to claim human rights for themselves.

This overt theft of human rights by corporate entities paved the way for the rise of new commercial monopolies, the era of the Robber Barons, and now to NAFTA and WTO world courts run largely by corporations to which not only people but entire nations must submit. This has led to the new Tea Parties of Seattle and Genoa, and a growing concern among people the world over that American democracy has been hijacked by corporate interests.

To reverse this trend, we must examine and then roll back the bizarre idea promulgated by corporations that they are “persons” and should have full access to the Bill of Rights. Citizens across the world are working on campaigns to deny corporate personhood, hoping to restore governments to the control of “We, the People” by and for whom they were created.