Could Today's Crises Help America Reject Corporate Personhood?

Economic crises represent social and political transition points, times of great difficulty but also times of great opportunity - We now stand at the edge of one those rare windows in time

America is in the midst of an economic crisis and Russia and China seem hell-bent on pushing us to what may become a world war. We’ve been here three times before in the history of our country, and each one has heralded major changes in the nature and structure of our government.

As we watch corporations pour increasingly large amounts of money into politics, it’s a good time to reevaluate their role in governance and society. At the top of that list is the doctrine created out of whole cloth by the US Supreme Court in the late 19th century called “Corporate Personhood.“ It has become one of the most destructive forces in American politics.

In 1776, Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations was published and the U.S. Declaration of Independence was signed. This was no coincidence: both were broadly embraced reactions, in part, to a widespread economic depression that had begun in the previous decade.

England reacted to their economic distress with a series of efforts to raise revenue: the Stamp Act, the Townshend Acts, and the Tea Act (among others); the colonists reacted by defying the corporate power of the East India Company with the Boston Tea Party and the Declaration of Independence.

There was war and upheaval, and a new nation was born.

Fourscore (80) years later, Abraham Lincoln was a lawyer in private practice, working for the railroads. On August 12, 1857, he was paid $4800 in a check, which he deposited and then converted to cash on August 31. That was fortunate for Lincoln, because just over a month later, in the Great Panic of October, 1857, both the bank and the railroad were “forced to suspend payment.”

Of the 66 banks in Illinois, The Central Illinois Gazette (Champagne) reported that by the following April, 27 of them had gone into liquidation. It was a depression so vast that the Chicago Democratic Press declared at its start, the week of Sept. 30, 1857, “The financial pressure now prevailing in the country has no parallel in our business history.”

Soon there was war and terrible upheaval: four years later the nation was split asunder by the Civil War. A transformed and more powerful federal government emerged, changing forever our government’s role in managing the country.

Eighty years later the Great Depression bottomed out as Hitler rose to power and again America experienced war and upheaval, on a greater scale than ever before, accompanied by dramatic transformations in the role and nature of our federal government.

Today we’re approaching that same interval — it’s been 77 years since the end of World War II — and people are nervous about another worldwide economic crisis, with good reason.

Even beyond the immediate consequences, economic crises have led to huge and long-term political changes. They have ushered in the rise of fascism, the consolidation of communism, the overthrow of monarchy (the American and French revolutions, for example), and the creation of the new and experimental democratic republic of the United States of America.

But what will come out of this time of danger/opportunity? What sort of future can we fashion? Will we use the crisis to create positive change and save the climate for our children and grandchildren, or allow forces of raw corporate power to have their way?

When Germany faced the last depression, its government turned to a hand-in-glove partnership with corporations (German and American) to solidify its power over its own people and wage war on others. Italy’s Benito Mussolini named this new form of corporate/state partnership fascism, referring to the old Roman fascia, or bundle of sticks held together with a rope, that was the symbol of the power of the Caesars.

This time, Mussolini said, the bundle was the police and military power of the state combined with the economic power of industry. During the 1920s and 1930s that fascist system was adopted by Italy, Spain, Japan, and Germany.

Mussolini also noted that there was a more accurate word to describe his political/economic system: “Fascism should more appropriately be called corporatism,” he wrote in the Encyclopedia Italiana, “because it is a merger of state and corporate power.” And indeed, the results of fascism can look very good, at first; in Germany it worked so well that Adolf Hitler was named TIME magazine’s Man of the Year on February 2, 1939.

But democracy is rarer than we think.

We think of our “western” civilization as having a democratic heritage, but that’s a mirage. For most of these thousands of years, kings, emperors, Caesars, popes, and warlords have ruled the lives of ordinary people.

Democracy was tried for just 185 years, from 507 BCE to 322 BCE, in Athens; the experiment came to a bloody end with the conquest of the area by warlord Alexander the Great.

The idea lay dormant for two thousand years; the rule of kings and warlords resumed, until the American experiment birthed it again — in the midst of an economic crisis.

There have been just four of these 80-year, four-generation economic cycles in our nation’s history, and all three of the previous ones threatened the very foundations of human liberty.

Yet as rare as democracy is in history, the concept is immensely compelling to the human spirit, and American expressions of the ideal have been the beacon that has lit the path forward for more than two centuries. From the French Revolution in 1789 to the people’s uprising in Beijing in 1989, people around the world have used language and icons from the pens of Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Paine, Thomas Jefferson and their peers.

The Greek-Roman-Masonic-Iroquois-American idea of a government “deriving its just powers from the consent of the governed” is one of the most powerful and timeless ideas in the world, even if we didn’t quite get it right at first (it was only true for propertied white males), and even if it’s been strained since its inception.

On May 29th, 1989, over twenty thousand people gathered around a 37-foot-tall paper mache statue in Beijing’s Tienanmen Square. They placed their lives in danger, but that statue was such a powerful archetypal representation that many were willing to die for it…and some did. They called their statue the “Goddess of Democracy”: it was a scale replica of the Statue of Liberty that stands in New York harbor on Liberty Island.

It is tremendously ironic that today some Republicans proudly assert that our “founding fathers” intended that political power only belong to the moneyed elite and the corporations they control. “America is not a democracy,” they say, “but just a republic.” The will of the people, they argue, doesn’t matter: billionaires and corporations should be running the show.

Is that a principle for which people would die in Tienanmen Square? No; they stood up for the goddess of democracy, inscribed with “Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free.” They demonstrated for the oppressed, and for their own hopes for personal freedom.

But while much of the world tries to emulate the American experiment, contemporary America is moving in the direction of the corporate-state partnership.

Executives from regulated industries are heading up the agencies that regulate them. Other symptoms of increasing corporate control of the nation include widespread privatization and so-called public-private partnerships: euphemisms for shifting control of a commons’ resources (like water or electricity) from government agencies to corporations.

Corporations and their agents have become the largest contributors to politicians, political parties, and so-called “think tanks” which both write and influence legislation.

That distinction between corporate control and human control is absolutely pivotal: governments that derive their just powers from the governed should be exclusively responsible to citizens and voters, and their agencies were originally created exclusively to administer and protect the resources of the commons used by citizens and voters.

Corporations are responsible only to stockholders and are created exclusively to produce a profit for those stockholders. When aggressive corporations control political power, however, the results are predictable.

We have recently seen, all too often, the strange fruits borne by placing a corporate sentry where a public guardian should stand: for instance, we now know that the California energy crisis of some years ago was manipulated into existence by energy companies to get rid of Democratic Governor Gray Davis.

The cost to humans for that corporate plunder was horrific, but a corporation that’s now been convicted of multiple deaths of Californians still has a stranglehold on that state’s energy.

How did it happen that corporations have the ability to do such things even when the public protests vigorously?

It turns out, says the Supreme Court, that corporations have human rights. In several different decisions, all grounded on an 1886 case, the Court has ruled that corporations are entitled to a voice in Washington and state capitols, the same as you and me.

Our nation was built on the ideal of equal protection of people (regardless of differences of race, creed, gender, or religion), and corporations are much bigger than people, much more able to influence the government, and don’t have the biological needs and weakness of people.

The path from government of, by, and for the people to government of, by, and for the corporations was paved largely by an invented legal premise embraced by the Supreme Court that corporations are, in fact, people, a premise called “corporate personhood.”

This doctrine states not just that people make up a corporation, but that each corporation, when created by the act of incorporation, is a full-grown “person” — separate from the humans who work for it or own stock in it — with all the rights granted to human persons by the Bill of Rights.

This idea would be shocking to the Founders of the United States.

James Madison, often referred to as “the father of the Constitution,” wrote:

“There is an evil which ought to be guarded against in the indefinite accumulation of property from the capacity of holding it in perpetuity by…corporations. The power of all corporations ought to be limited in this respect. The growing wealth acquired by them never fails to be a source of abuses.”

And in a letter to James K. Paulding, 10 March 1817, Madison made absolutely explicit a lifetime of thought on the matter.

“Incorporated Companies,” he wrote, “with proper limitations and guards, may in particular cases, be useful, but they are at best a necessary evil only. Monopolies and perpetuities are objects of just abhorrence. The former are unjust to the existing, the latter usurpations on the rights of future generations.”

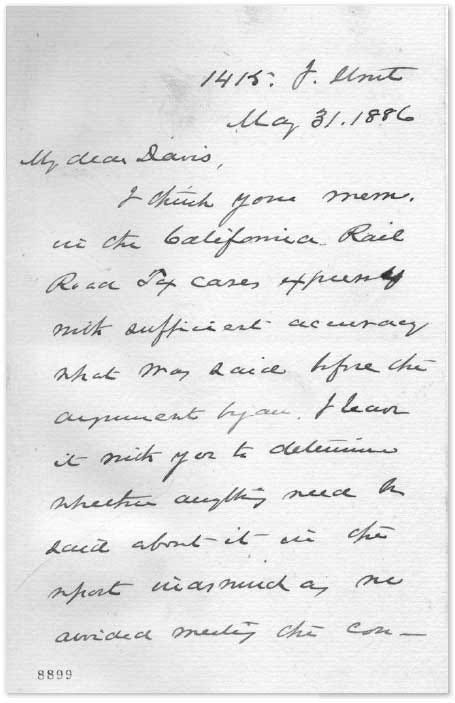

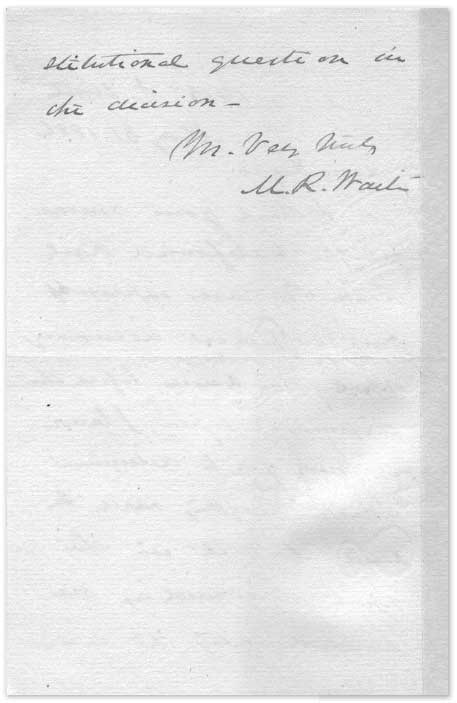

The concept of “corporate personhood” hasn’t been around forever; it arrived long after the death of James Madison (and the entire Revolutionary Era generation). It happened in 1886, when the U.S. Supreme Court’s reporter inserted a personal commentary called a headnote into the decision in the case of Santa Clara County v. Union Pacific Railroad.

For decades the Court had repeatedly ruled against the doctrine of corporate personhood, and they avoided the issue altogether in the 1886 Santa Clara case, but Court Reporter J.C. Bancroft Davis (a former corporate president) added a note to the case saying that the Chief Justice, Morrison R. Waite, had said that “corporations are persons” who should, Davis suggested, be granted human rights under the free-the-slaves Fourteenth Amendment.

Davis had recorded a remark made in a side conversation that was never part of a ruling by the Court; he phrased it in a way that implied it was part of the decision, but it wasn’t.

When I was writing my book on the 14th Amendment, Unequal Protection, searching the Library of Congress’ archives we found a note in Waite’s handwriting, specifically saying to Davis, “We avoided meeting the constitutional question in the decision.”

As far as I can tell, nobody had seen the document in over 100 years.

Nonetheless, the headnote for that decision, falsely claiming the Court ruled that corporations have rights as persons, was published in 1887 (a year Waite was so ill he rarely showed up in court; he died the next year).

Since then, corporations have claimed that they are persons — pointing to that decision and its fraudulent headnote — and, amazingly enough, in most cases the courts have agreed.

Many legal scholars think it’s because the courts didn’t bother to read the case but instead just read the headnote, which has no legal standing. But at this point, after a century of acceptance, the misreading has been repeatedly quoted by the Supreme Court itself, making it into real law.

The impact has been almost incalculable. As “persons,” corporations have claimed the First Amendment right of free speech and — even though they can’t vote — they now spend billions of dollars to influence elections, prevent regulation of their own industries, and write or block legislation.

Before 1886, in most states this behavior was explicitly against the law.

In Wisconsin, for example, on the eve of his becoming chief justice of Wisconsin’s Supreme Court, Edward G. Ryan said ominously in his 1873 address to the graduating class of the University of Wisconsin Law School:

“[There] is looming up a new and dark power…the enterprises of the country are aggregating vast corporate combinations of unexampled capital, boldly marching, not for economical conquests only, but for political power….

“The question will arise and arise in your day, though perhaps not fully in mine, which shall rule—wealth or man [sic]; which shall lead—money or intellect; who shall fill public stations—educated and patriotic freemen, or the feudal serfs of corporate capital….”

The Wisconsin legislature had recently put into law severe restrictions on corporate election interference:

Political contributions by corporations. No corporation doing business in this state shall pay or contribute, or offer consent or agree to pay or contribute, directly or indirectly, any money, property, free service of its officers or employees or thing of value to any political party, organization, committee or individual for any political purpose whatsoever, or for the purpose of influencing legislation of any kind, or to promote or defeat the candidacy of any person for nomination, appointment or election to any political office.

Penalty. Any officer, employee, agent or attorney or other representative of any corporation, acting for and in behalf of such corporation, who shall violate this act, shall be punished upon conviction by a fine of not less than one hundred nor more than five thousand dollars, or by imprisonment in the state prison for a period of not less than one nor more than five years … and if a foreign or non-resident corporation its right to do business in this state may be declared forfeited. (emphasis added)

And it wasn’t just Wisconsin: every state had similar laws to limit corporate power, particularly when it came to inserting themselves in politics.

Pennsylvania corporate charters were required to carry revocation clauses starting in 1784; and in 1815 Supreme Court Justice Joseph Story said explicitly that corporations existed only because they were authorized by state legislatures. In his ruling in the Terrett v. Taylor case, he wrote:

“A private corporation created by the legislature may lose its franchises by a misuser or nonuser of them….This is the common law of the land, and is a tacit condition annexed to the creation of every such corporation.”

It was a concern the nation shared. As President Grover Cleveland said in his annual state of the union address immediately following the Santa Clara decision:

“As we view the achievements of aggregated capital, we discover the existence of trusts, combinations, and monopolies, while the citizen is struggling far in the rear or is trampled to death beneath an iron heel. Corporations, which should be the carefully restrained creatures of the law and the servants of the people, are fast becoming the people’s masters.”

Since the 1890s, however, corporations have repeatedly and successfully sued to have these “unequal” restrictions removed, based on that phony headnote in the Santa Clara case.

As a “person,” corporations can (and do) claim the Fourth Amendment “right of privacy” and prevent government regulators from performing surprise inspections of factories, accounting practices, and workplaces, leading to uncontrolled pollution and hidden accounting crimes.

Before 1886 concealing corporate crimes was also, in most states, explicitly against the law. Ironically, corporations have also successfully claimed that when people come to work on their “corporate private property,” those very human people are agreeing to give up their own constitutional rights to privacy, free speech, and even to the control of their own possessions.

As a “person,” corporations can claim that when a community’s voters pass laws to ban them, those voters are engaging in illegal discrimination and violating the corporation’s “human rights” guaranteed in the Fourteenth Amendment — even if the corporation has been convicted of felonies.

The result has been an Alice In Wonderland situation where a corporation convicted of felonies can and did own television stations (GE, for example, was convicted of multiple felonies but owned many television stations), but when a human being in the Midwest was convicted of a felony the FCC moved to strip him of his TV station.

The terrible irony is that corporations insist on the protections owed to humans, but not the responsibilities and consequences borne by humans.

They don’t have human weaknesses: don’t need fresh water to drink, clean air to breathe, uncontaminated food to eat, and don’t fear imprisonment, cancer, or death.

Granting personhood to corporations is an absolute perversion of the principle cited in the Declaration of Independence, which explicitly states that the government of the United States was created by people and for people, and operates only by consent of the people whom it governs. The Declaration states this in unambiguous terms:

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness. That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.”

The result of corporate personhood has been the relentless erosion of government’s role as a defender of human rights and of government’s responsibility to respond to the needs of its human citizens.

Instead, we’re now seeing a steady insinuation of corporate representatives and those beholden to corporations into legislatures, the judiciary, and, with CEO’s Trump, Bush, and Cheney, even the highest office in the land.

We’ve reached the point in the United States where corporatism has nearly triumphed over democracy.

If events continue on their current trajectory, the ability of our government to respond to the needs and desires of humans — things like fresh water, clean air, uncontaminated food, independent local media, secure retirement, and accessible medical care — may vanish forever, effectively ending the world’s second experiment with democracy.

We will have gone too far down Mussolini’s road, and most likely will encounter similar consequences, at least over the short term as we saw beginning to emerge during the Trump presidency: a militarized police state, a government unresponsive to its citizens and obsessed with secrecy, a ruling elite drawn from the senior ranks of the nation’s largest corporations, and the threat of war.

Alternatively, if we reverse the 1886 fraud that created corporate personhood, it’s still possible we can return to the democratic republican principles that animated our Founders and brought this nation into being.

Our government — elected by human citizen voters — can shake off the neoliberal experiment of the past forty years with its exploding corporatism, and throw the corporate agents and buyers-of-influence out of the hallowed halls of Congress.

We can restore our stolen human rights to humans, and keep corporate activity constrained within the boundaries of that which will help and heal and repair our Earth rather than plunder it.

The path to doing this is straightforward. Citizens across the nation are looking into the possibility of passing local laws denying corporate personhood, and increasing numbers of Democratic politicians are looking for ways to correct the Supreme Court’s reporter’s 1886 lie and its spawn, like Citizens United.

Taking another path, some are suggesting that the Fourteenth Amendment should itself be amended to insert the word “natural” before the word “person,” an important legal distinction that will sweep away a century of legalized corporate excesses and reasserting the primacy of humans.

Congress could also exercise its Article 3 Section 2 power and tell the Supreme Court that corporations are not persons and that is an “exception” to the Court’s ability to create doctrine without congressional consent.

An expanded Supreme Court could even take up this issue, along with its bizarre twin, the Court-created doctrine that money is the same thing as speech.

The concern is not corporations per se; the bludgeon of corporate personhood is rarely used by small or medium companies; it’s used almost exclusively by a handful of the world’s largest, to force their will on governments and communities.

This means a very small number of parties (the biggest corporations) are all that stand in the way of reform, which suggests the corporate personhood doctrine is the weakest link in the chain of corporate power.

And it’s a link that can be broken by alert and activist citizens, thus steering America away from Mussolini’s view of government and back on course toward that of our nation’s Founders. What is required is that we undo that 1886 court reporter’s incorrect headnote, by any of the various means people are beginning to try.

Corporations don't need pure food, clean air, or safe drinking water, but they have the ability to influence our government and elections. To rescue democracy, America must reject the bizarre Supreme Court-created doctrine of "corporate personhood."

Once again in America, we must do what the author of the Declaration of Independence always hoped we would:

“[T]he people, being the only safe depository of power, should exercise in person every function which their qualifications enable them to exercise, consistently with the order and security of society.” (emphasis added)

We must seize this moment to take back from corporations the power to govern, for the world our children and our children’s children will inherit.

Well that quote from President Cleveland says it all by describing corporations as " creatures of the law". That's what they are and always have been, a legal construct, in some cases no more than an idea.

The history of how all these awful decisions get reinforced layer by layer simply to serve the rich and powerful is always mind-blowing.

So is the concept that humanity must put itself through 80 years of repression to get to a turning. There is no arguing with the evidence that it's true. It's a privilege to live through one?

Good grief, the stuff I have learned from "taking your classes", Thom!

Once again, thanks for a great Report. I'm in awe at your ability to access the historical records and to present your argument in such a readable, logical and heartfelt manner.

One thing about democracy, even more so than other forms of government, is that it seems to rely on human civility -- people who'll work together towards an ideal, even if it means they don't always get their way; there's a fragile balancing act in that, which elevates the importance of the scales of justice. What the people want, ideally, is the "promised land" of peace and prosperity. Judging by what's going on today, that's no longer the case, neither economically or justly.

You're right in saying that democracy appeals to the spirit of the people. That makes it a target for the forces in our world who manipulate people to get what they want. Your mention of China and Russia as representatives of these forces is correct.