Should a Handful of Billionaires Own More Wealth than the Bottom 50% of All Americans?

Is our economy here to serve average Americans, or are we here to serve those who own and control most of the money flowing through our economy?

At the urging of Republican Senators Hawley and Rubio, a new think tank is working out ways for the GOP to change their messaging.

They want to shift their rhetoric from support for corporations and the morbidly rich to pretending they care about working people. This new organization will, they say, “think differently about labor vs. capital than Republicans have in recent generations.”

It’s a cynical effort to capture Trump’s working class base. He’d promised he’d bring our jobs home from China, empower labor unions, raise taxes on the rich so high that “my friends won’t ever talk to me again,” and give every American full health insurance that cost less than Obamacare. Those promises helped win him the White House.

All were lies, but the GOP base bought it and gave him tens of millions of votes; now Hawley, Rubio, et al think they can bottle that populist rhetorical magic and repeat Trump’s shtick for 2024.

Which raises the existential question both economists and politicians have debated for centuries:

Why do nations create and sustain economies? Is the economy here to serve average Americans, or are working class people here to serve those who own and control the economy?

America has had two different but clear answers to that question during the past century.

From the end of the Republican Great Depression with Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal in the 1930s until 1981 (including the presidencies of Republican Presidents Eisenhower and Nixon, who maintained the top 91% and 74% income tax rates), the answer was unambiguous: “The economy is here to serve average Americans.”

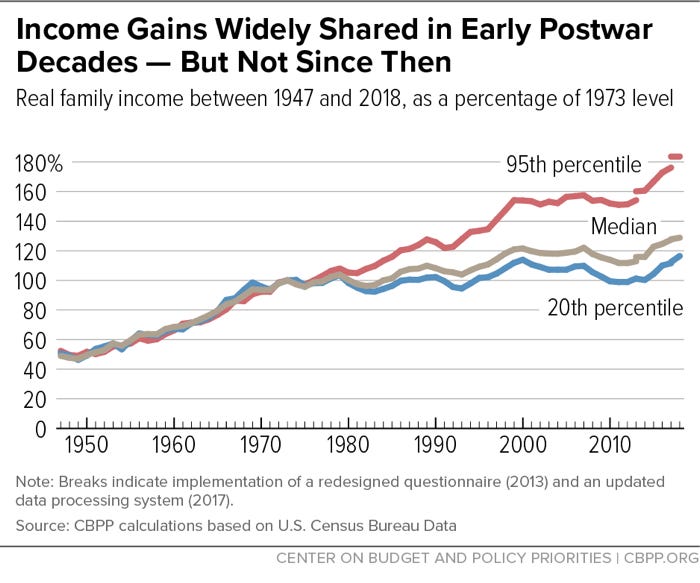

Income and wealth during that time rose at about the same rate for working class Americans as they did for the rich, something we’d never before seen in this country.

This was not an accident or a mistake. It was the very intentional outcome of policies put into place by FDR and then maintained by both Democratic and Republican administrations for almost 50 years during that pre-Reagan era.

And then came the Reagan Revolution, when Republicans decided that the middle class wasn’t as important as giant corporations and the very wealthy after all, and that the rest of us are here to serve the rich.

The Center for Budget and Policy Priorities, a non-partisan research and policy institute, captured this change in sentiment and policy in a graphic from their 2020 Guide to Statistics on Historical Trends in Income Inequality:

Qui bono is the question in legal terms: who benefits?

We put massive effort into creating and maintaining our economy, from laws to courts to regulatory agencies to creating and maintaining a stable currency and building out transportation across the country at government expense.

Who should benefit from this massive national undertaking?

Should it be a handful of billionaires, three of whom today own more wealth than the bottom half of all Americans? Is it a good thing for our society and nation that one single millennial billionaire owns more wealth than all other millennials in America combined?

Or should we allow — even encourage — people building businesses and getting rich, but also use tax policy and regulation to impose limits on how rich they can become and how they can use those riches to manipulate our political system?

Progressive Republican President Teddy Roosevelt was the first to turn this question into legislation, proposing what later became the Income Tax (1913), the Tillman Act (1907), and the Estate Tax (1913).

In 1920, Republican Warren Harding won the White House on the platform of “a return to normalcy,” suggesting it was time to drop the income tax from the World War I level of 90% down to 25%, which he did.

It kicked off the “Roaring 20s” that F. Scott Fitzgerald chronicled in The Great Gatsby, when the rich got massively richer while working people lost ground and private police murdered union organizers on behalf of wealthy industrialists. It led us straight to the Great Crash of 1929 and the Republican Great Depression.

FDR stepped into the gap in 1933 and began raising that tax rate on the richest of the rich back up to an eventual 91%, where it remained until Lyndon Johnson dropped it to 74% (but closed so many loopholes in the same legislation that rich people actually paid more taxes the following year than they had before).

Reagan then took it down to 25% for a year and then up to 27%; today it’s 37%. The period from 1981 to today shows what happens when great wealth isn’t regulated through rational taxation.

The long-term consequence of Reagan’s decision has been a $50 trillion transfer of wealth from the homes and bank accounts of working class people into the money bins of the top 1 percent.

It took the American middle class from two-thirds of us in 1980 down to 45% of us today. To maintain middle-class status now generally requires two workers in a family; it only required one full-time worker when Reagan stepped into the White House.

This question of the relationship between a nation’s economy and its working people has tormented thoughtful economists since Scottish philosopher and economist Adam Smith published his brilliant Theory of Moral Sentiments in 1759.

Writing a century before Sigmund Freud was born, Smith essentially identified what Freud would later call the Superego, that part of our mind that recognizes right and wrong and restrains us from behaving in ways that injure others.

Smith called it the “inner man,” capable of being an “impartial spectator” offering “moral” advice within our own minds.

He believed that in the battle between greed and compassion, compassion nearly always won out. The problem was the “nearly” part of that.

If even a small number of Honoré de Balzac’s “great fortunes that come from great crimes” seize control of a nation’s politics and thus its economics, that nation will, Smith said, always turn the nation to supporting the rich instead of the poor and working class:

“When our passive feelings are almost always so sordid and so selfish, how comes it that our active principles should often be so generous and so noble?” Smith asked in Theory.

“[W]hat is it which prompts the generous, upon all occasions, and the mean upon many, to sacrifice their own interests to the greater interests of others? It is not the soft power of humanity, it is not that feeble spark of benevolence which Nature has lighted up in the human heart, that is thus capable of counteracting the strongest impulses of self-love.

“It is a stronger power, a more forcible motive, which exerts itself upon such occasions. It is reason, principle, conscience, the inhabitant of the breast, the man within, the great judge and arbiter of our conduct.”

Smith, who would revolutionize the world of economics with his 1776 masterpiece The Wealth of Nations, knew that most people actually derived pleasure and happiness from helping others, even when it meant a certain amount of self-sacrifice:

“How selfish soever man may be supposed, there are evidently some principles in his nature which interest him in the fortune of others, and render their happiness necessary to him, though he derives nothing from it except the pleasure of seeing it.”

That said, Smith was no dreamy-eyed idealist. He knew that greed also lived in the human heart, and, when society didn’t put up guardrails to protect the rest of us from the greed of the rich and powerful, it would corrupt the nation and impoverish the majority of the people:

“This disposition to admire, and almost to worship, the rich and the powerful, and to despise, or, at least, to neglect persons of poor and mean condition … is, at the same time, the great and most universal cause of the corruption of our moral sentiments.”

Now that Americans are increasingly figuring out that the neoliberal Reagan Revolution produced a great — to use Smith’s word — corruption of America, the challenge remains to seize back from the morbidly rich their control over our politics and policies, particularly tax and labor policies.

Republicans are now trying to pretend they’re with workers’ on this issue of wealth and income. As “Speedy” Josh Hawley wrote two weeks ago:

“[I]f conservatives care about healthy towns and schools and churches, as they always say they do, they should support the kind of work and wages that nourish those institutions and make them possible.”

Riiigghht. They’ll give lots of lip service to “reinventing” the GOP between now and November 2024, but that’s all it’ll be. American working people still confront, in the GOP, a political party that is completely in the bag for great wealth.

Challenging the primacy of that wealth is going to be particularly difficult because five corrupt Republicans on the Supreme Court have legalized political bribery with Citizens United, but history shows it’s not impossible. Such bribery was also fully legal in 1932, when FDR swept the election and put the rich and powerful in their place.

“They hate me,” he told a crowd in 1936, “and I welcome their hatred.”

We have a long way to go to restore what President Harry Truman called “morality in government.”

This is a struggle that’s been going on for longer than most of us have been alive, as you can hear from President Truman himself in this 2-minute clip from March 29, 1952:

But if we can wake enough Americans to the true situation, it’s not beyond our reach.

Once again , ‘the truth will set you free’ .

But the Republicans for hundreds of years have supported the rich at the expense of the middle class and the poorest. The fact that people w the highest incomes in our nation pay meager taxes so the rest of the country can make them richer is truly an evil illness.

The twisted minds of these people and their supporters confirms what we’ve always known

I love the phrase 'morbidly rich' because ultimately, greed and avarice will kill you. Look at Elon Musk; I remember years ago, when he just started Tesla, he appeared on a morning show with his first wife and family (young children at the time). He was an earnest, rather sweet genius who had all sorts of ideas to address our climate crisis. Fast forward; smokes way too much weed and is at times a paranoid psychopath. Greed will do that to you. I believe that Smith would agree; you cannot serve God and mammon, you must love one and despise the other. Do a deep dive on the etymology of the word 'mammon' - it means more than just money.